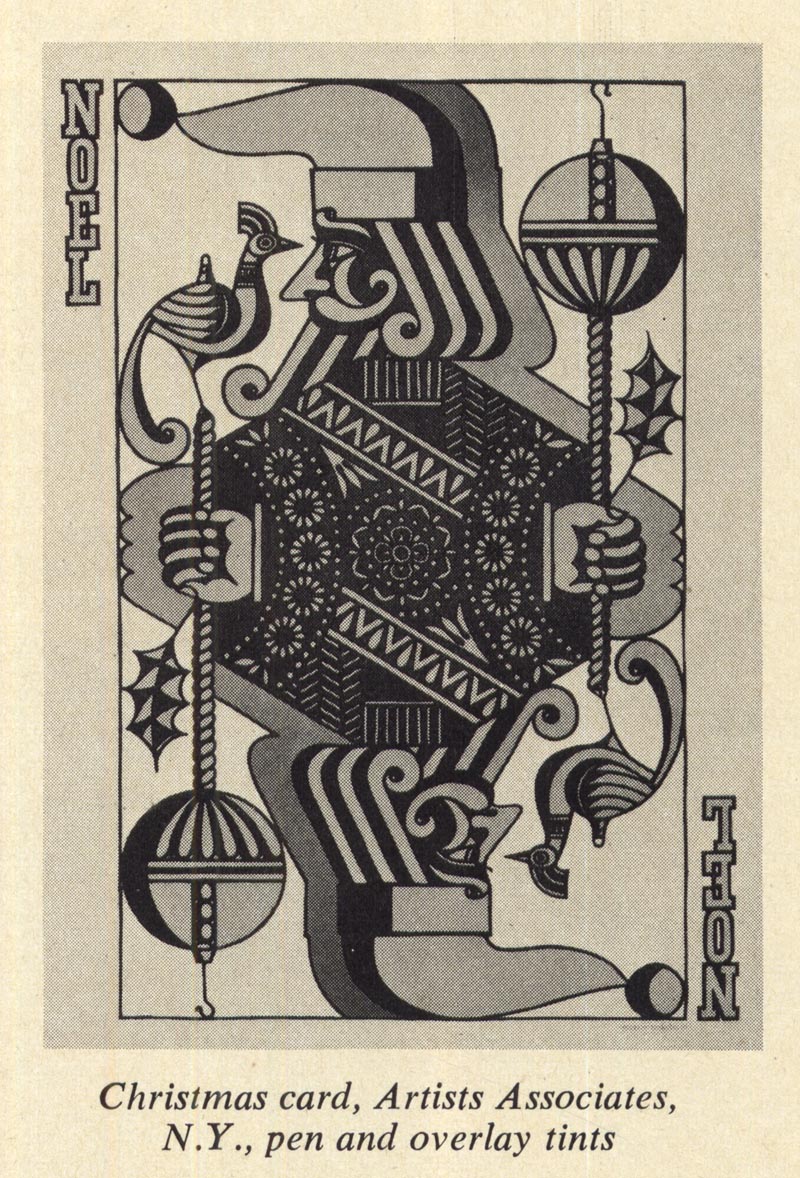

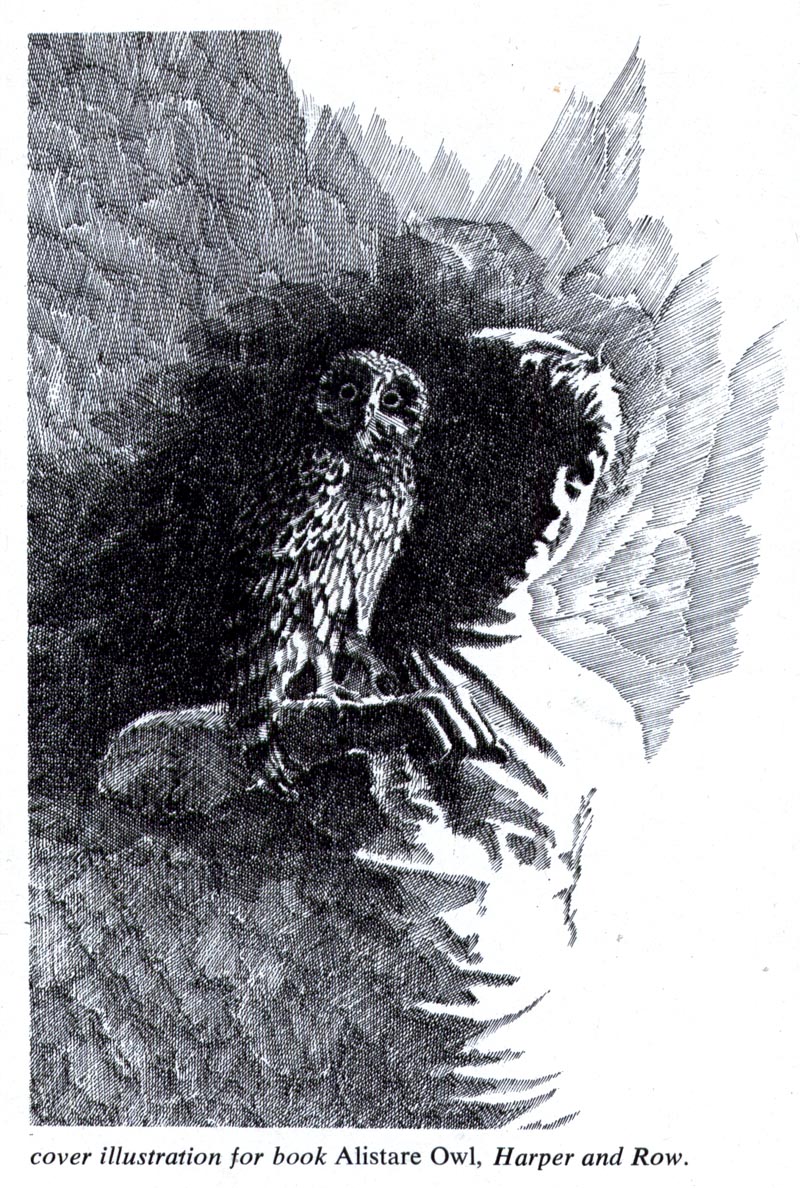

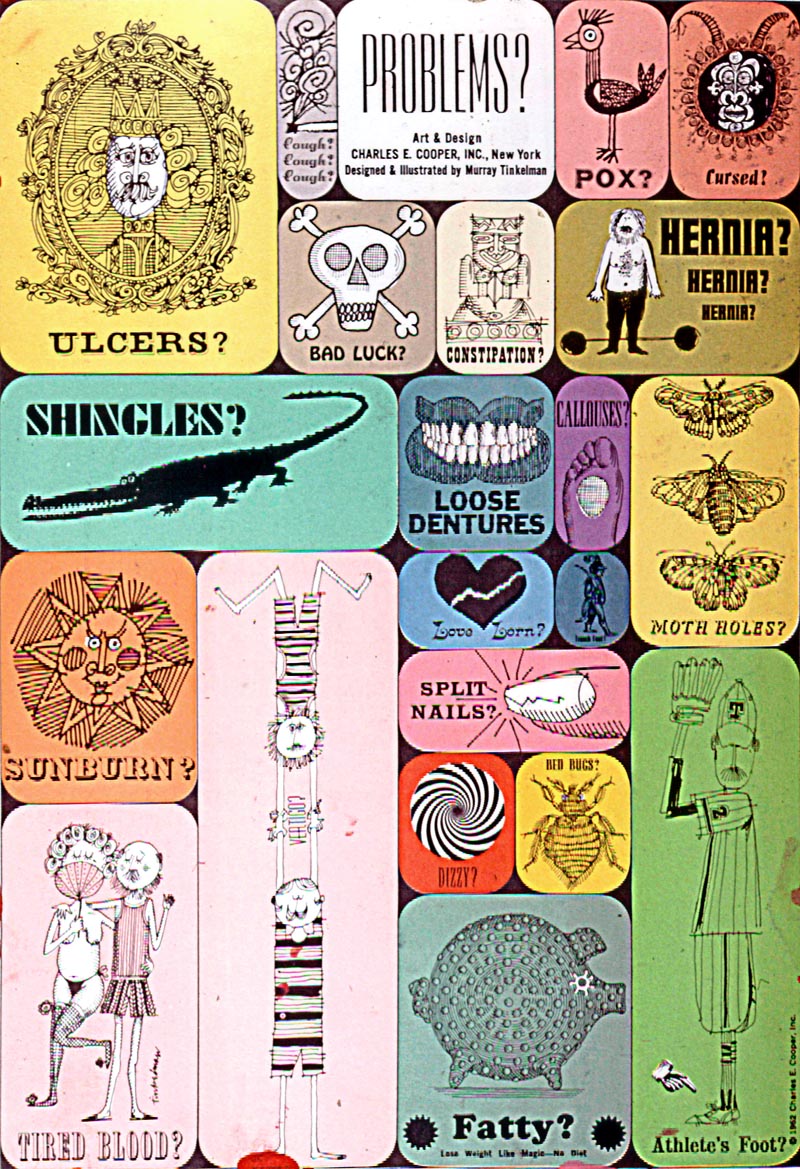

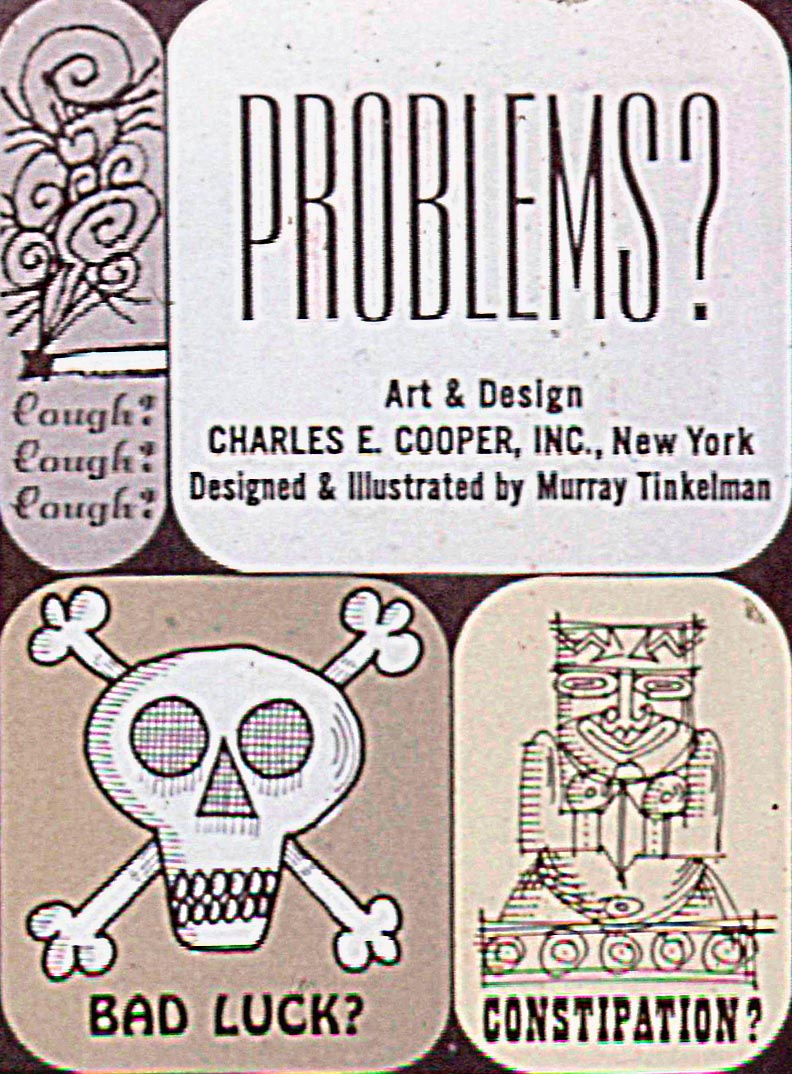

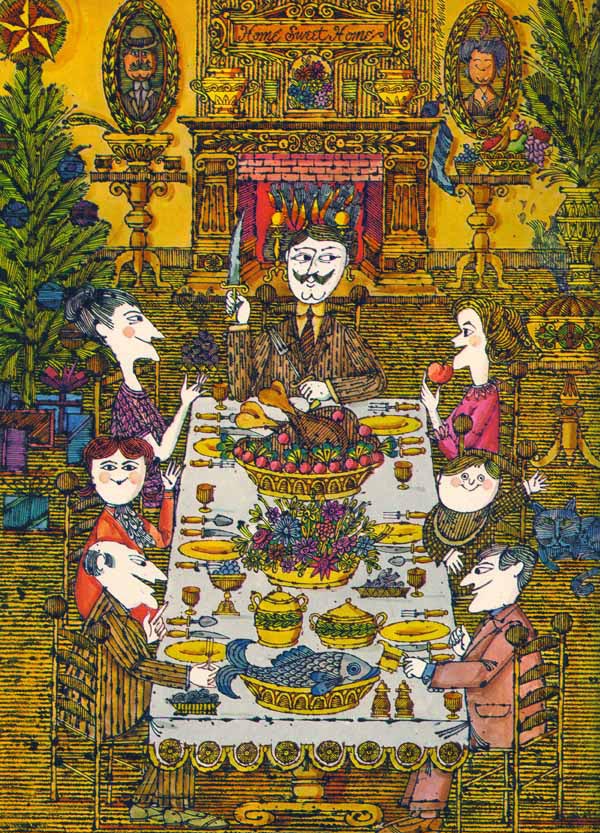

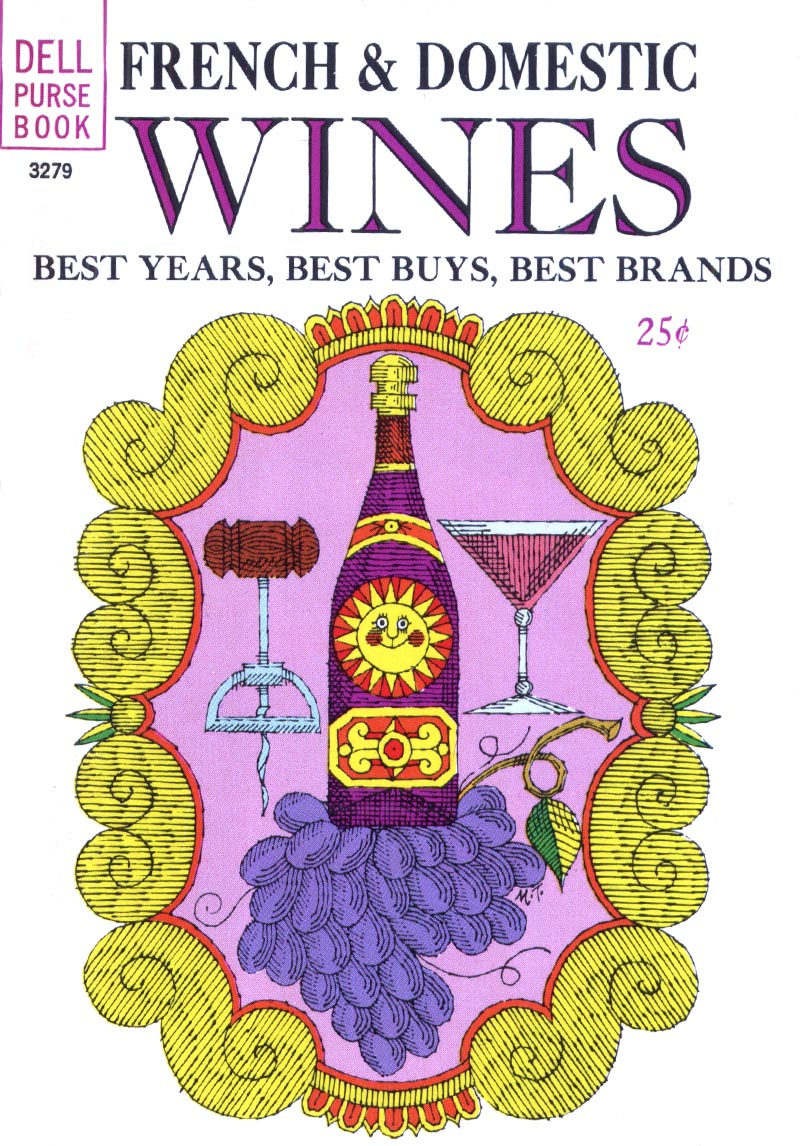

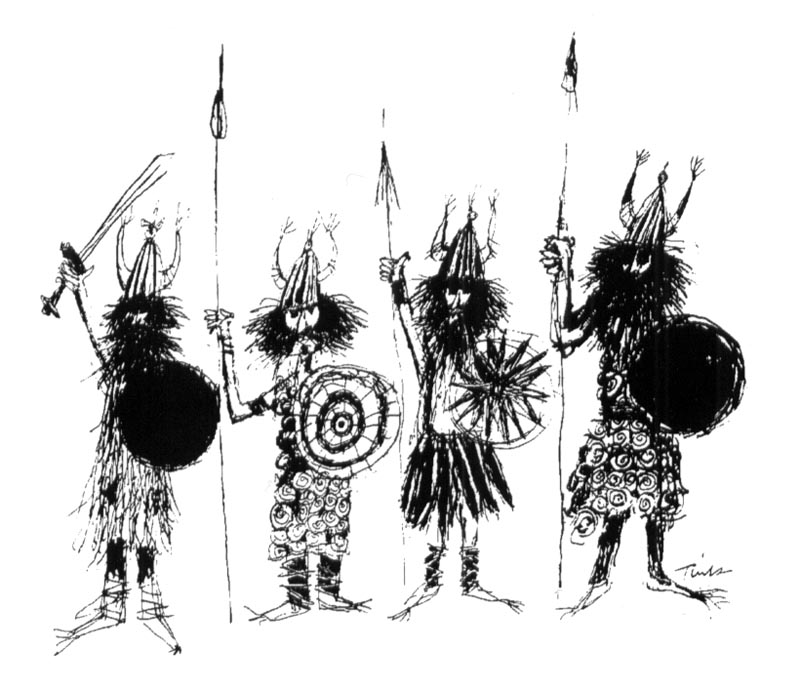

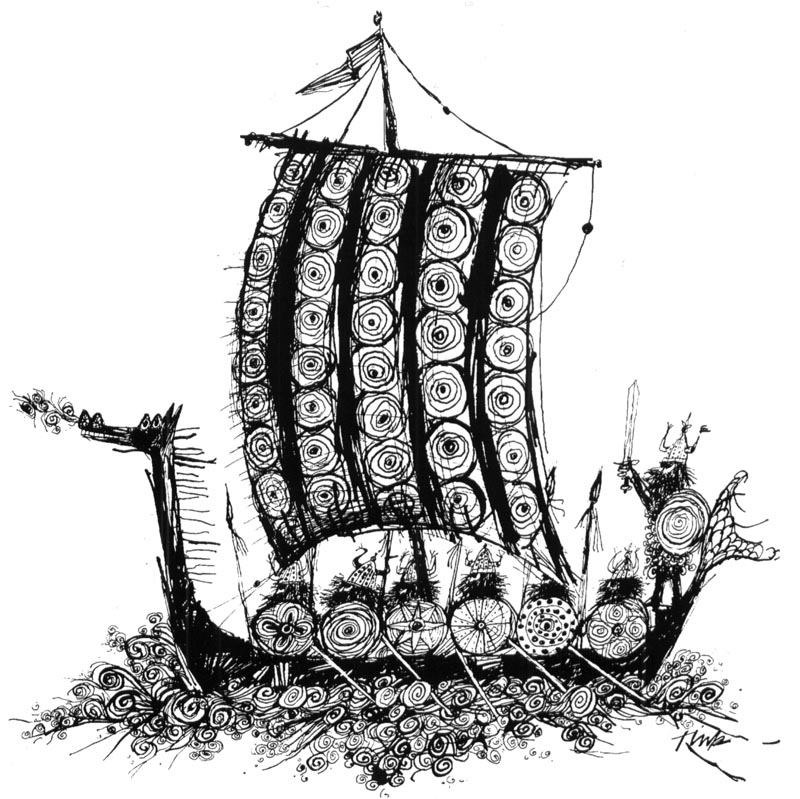

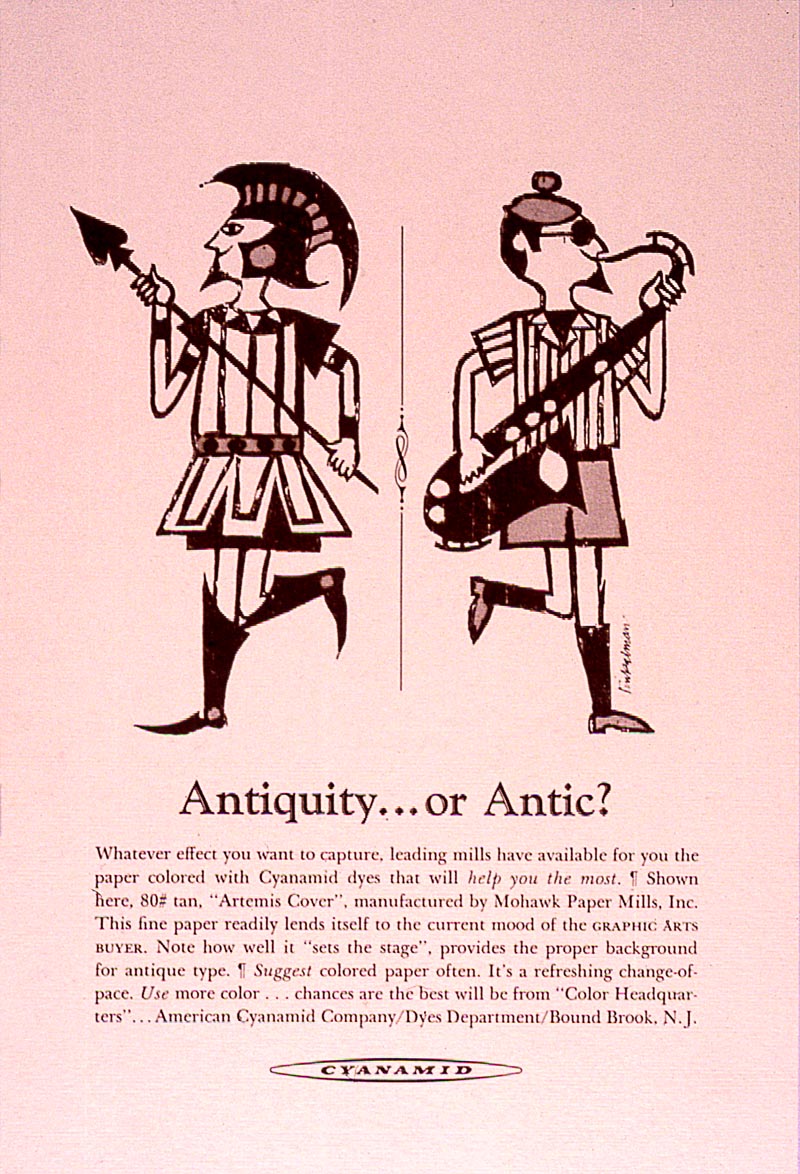

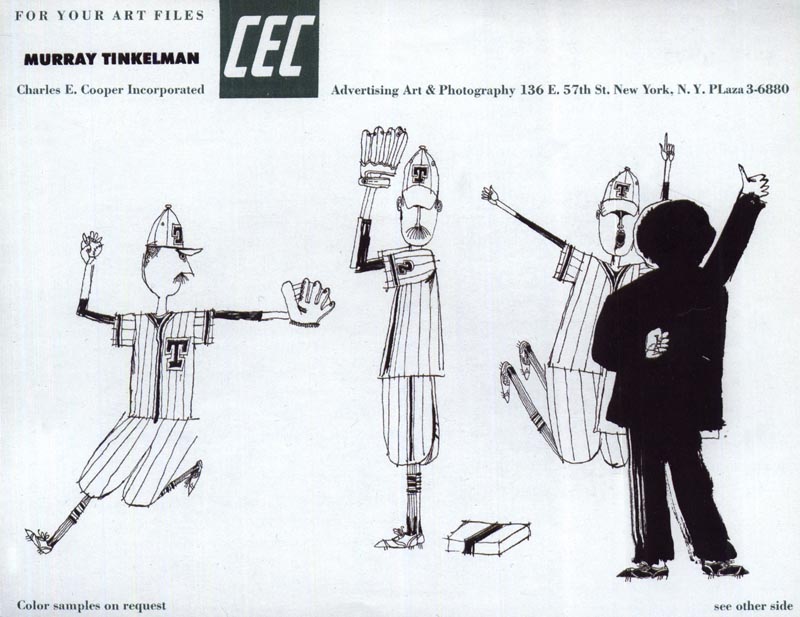

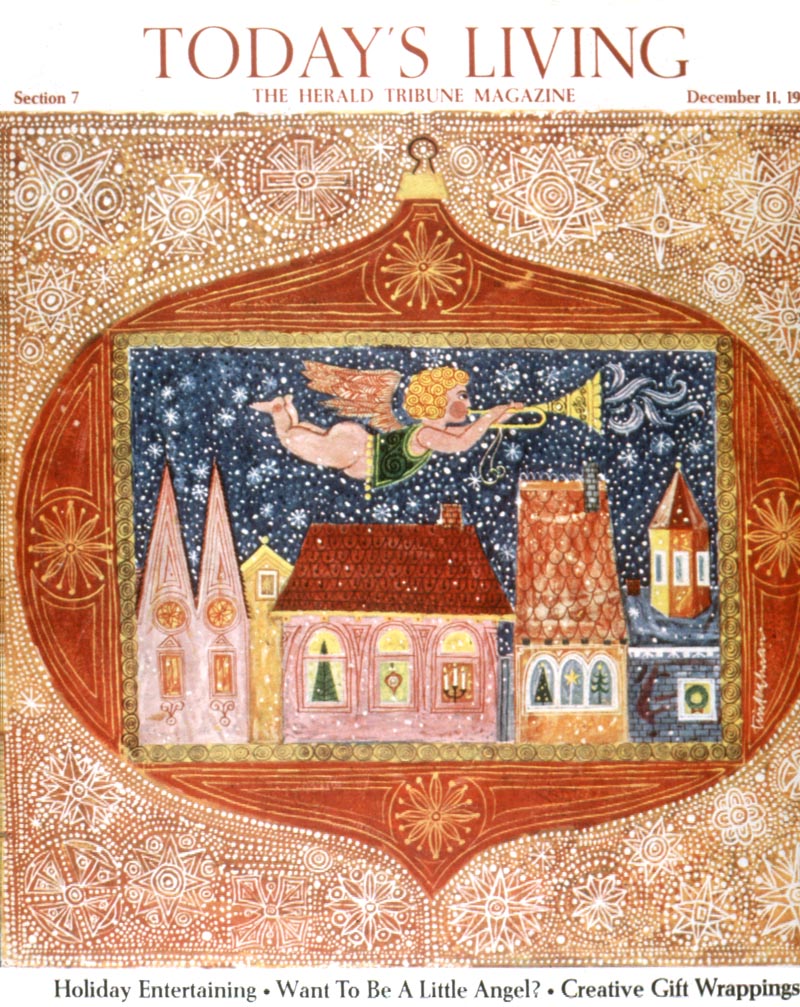

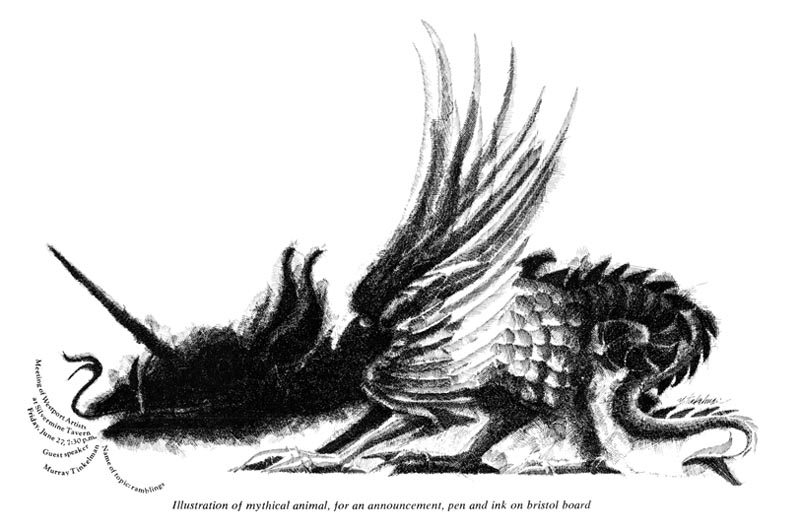

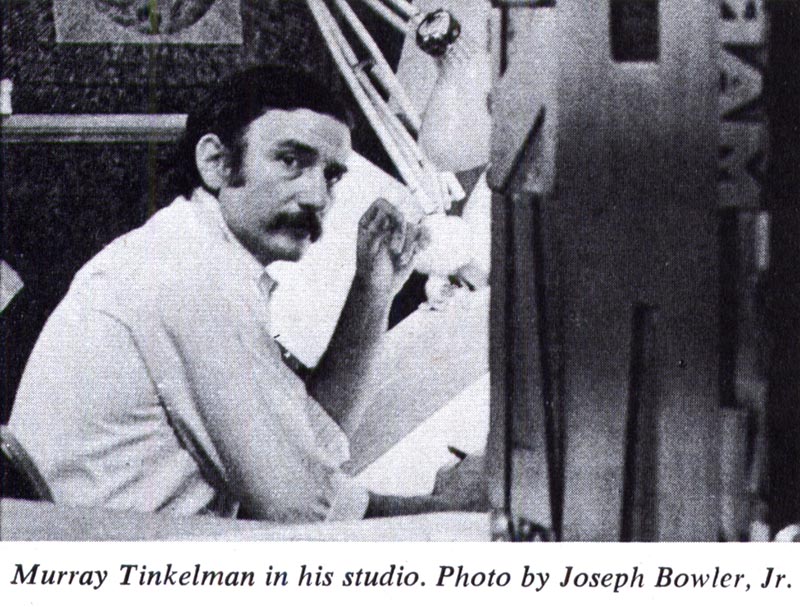

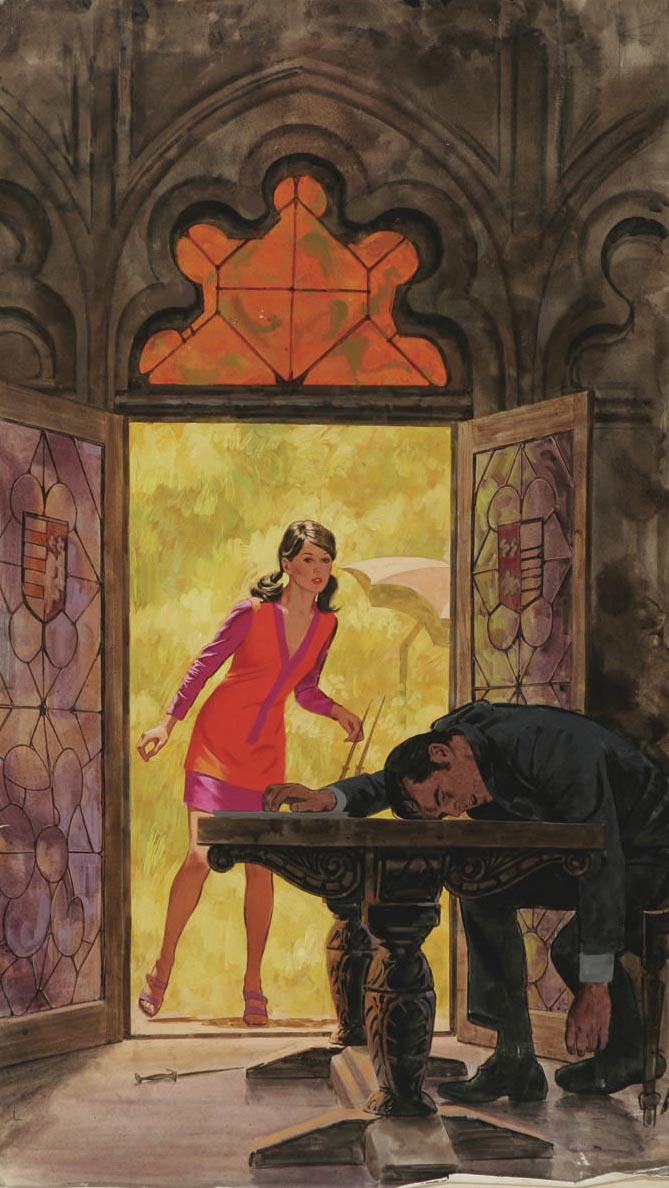

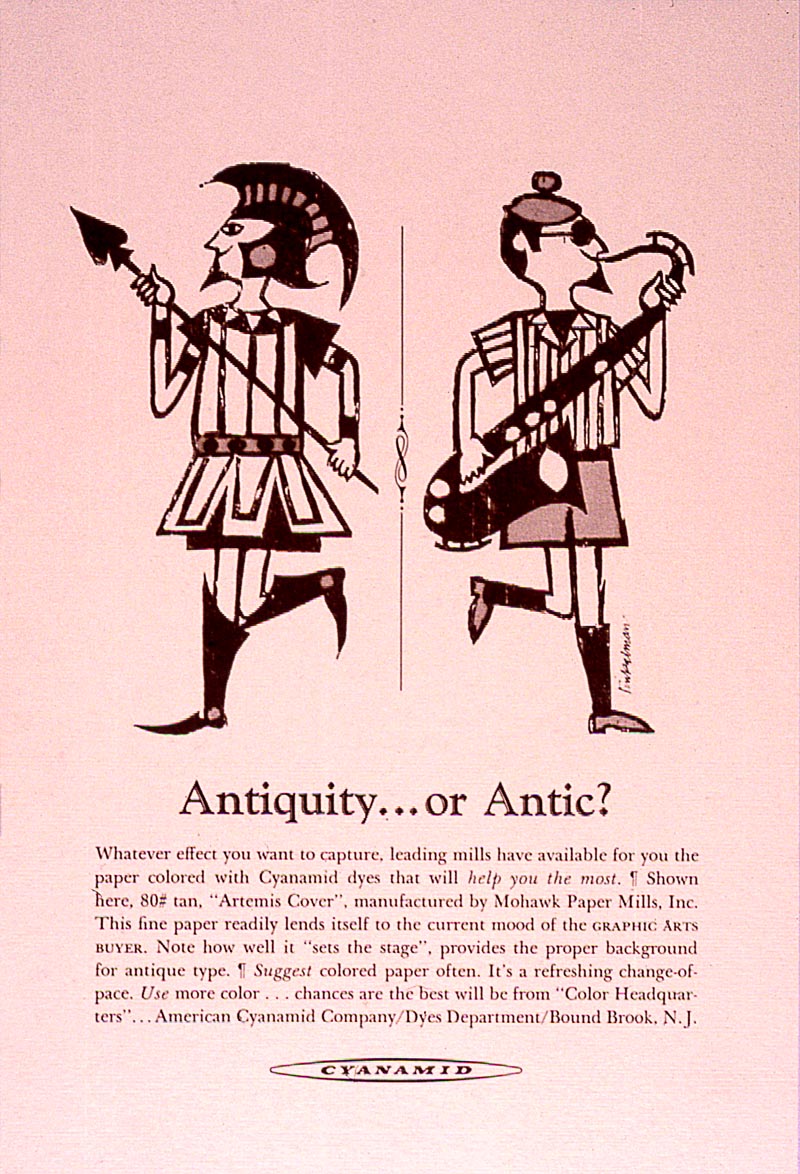

This is Murray Tinkelman...

... and this is Murray Tinkelman...

... and this is Murray Tinkelman too.

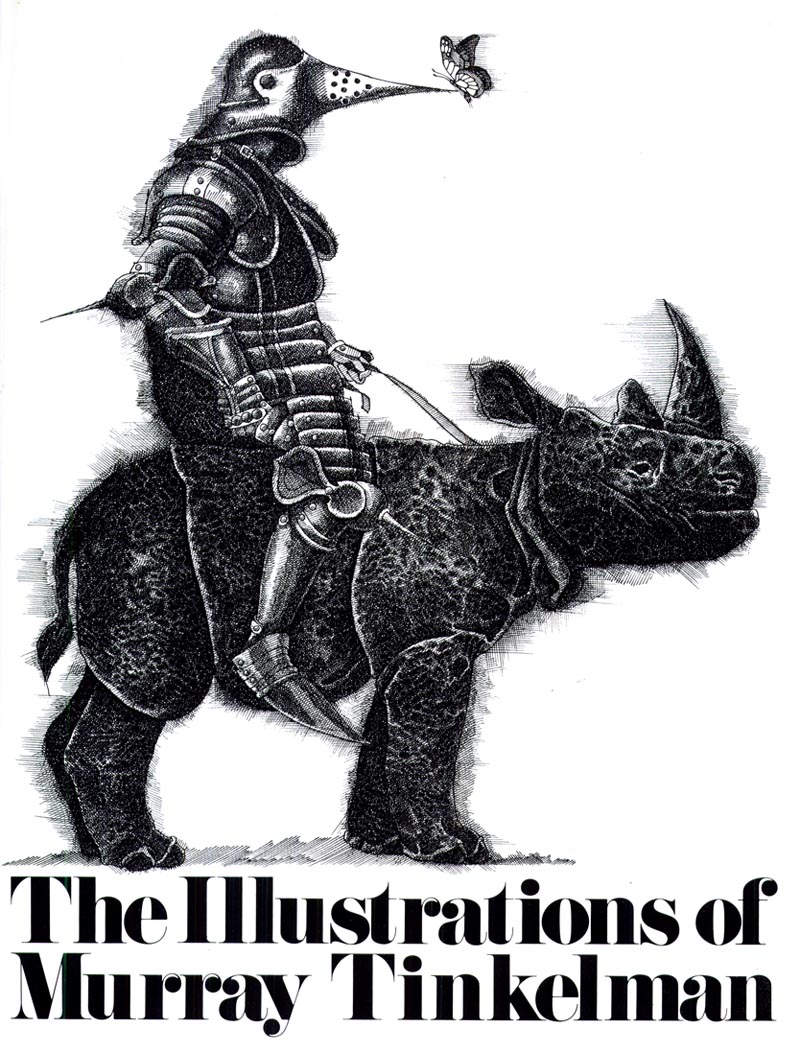

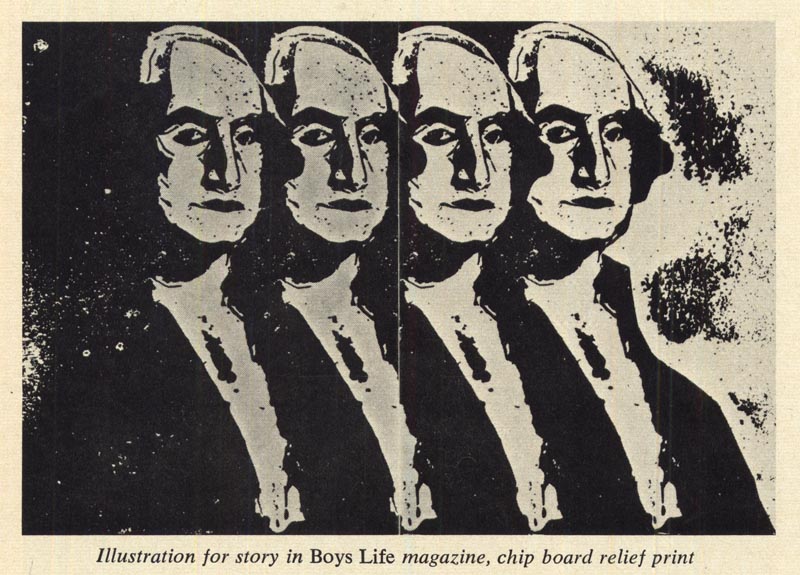

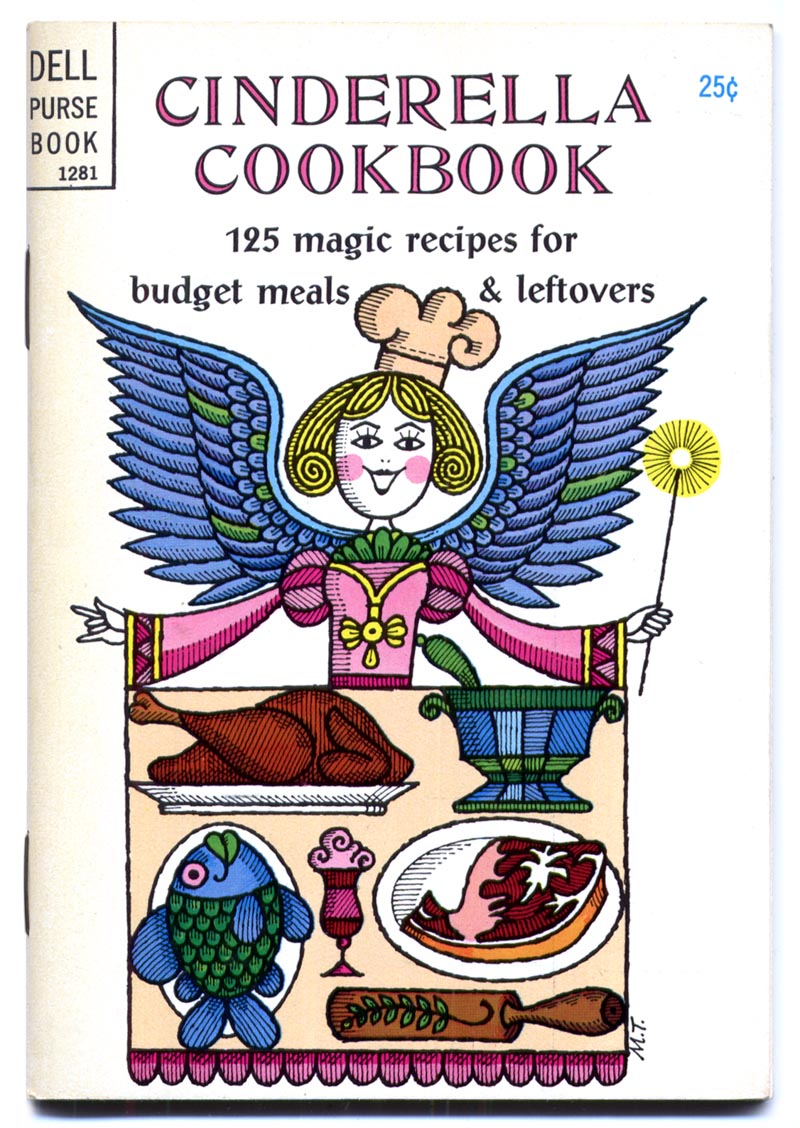

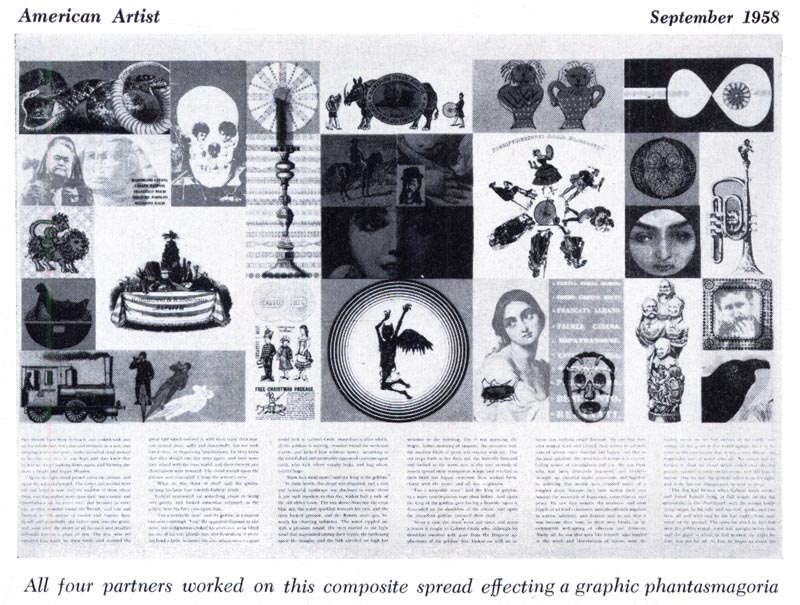

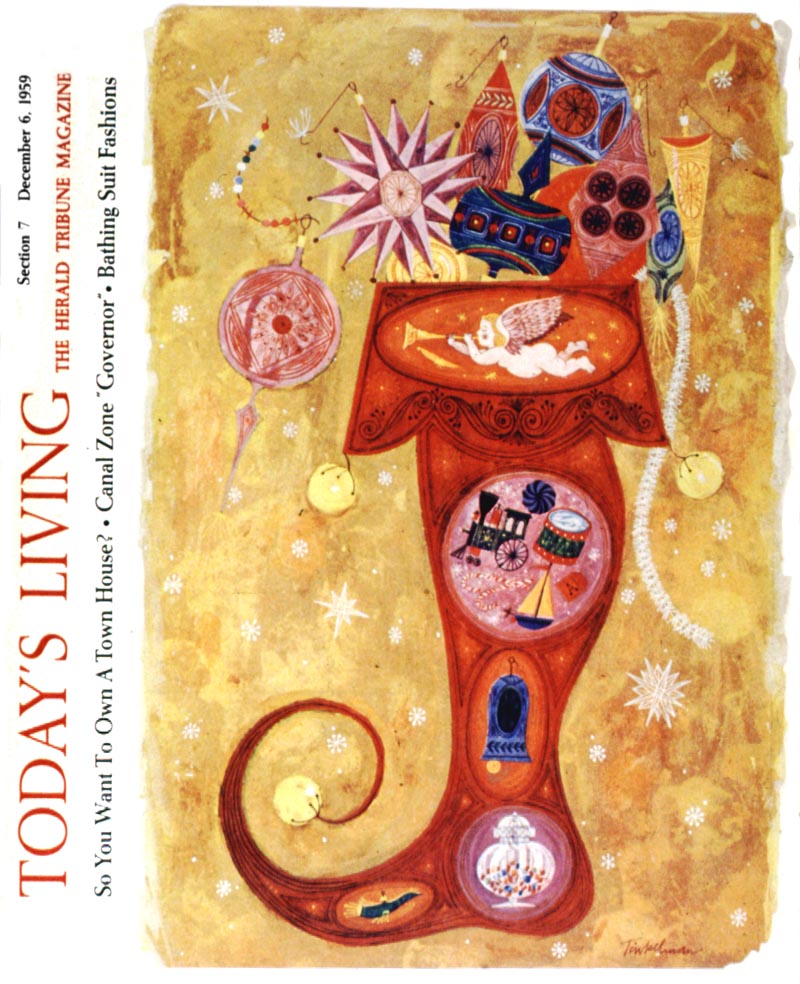

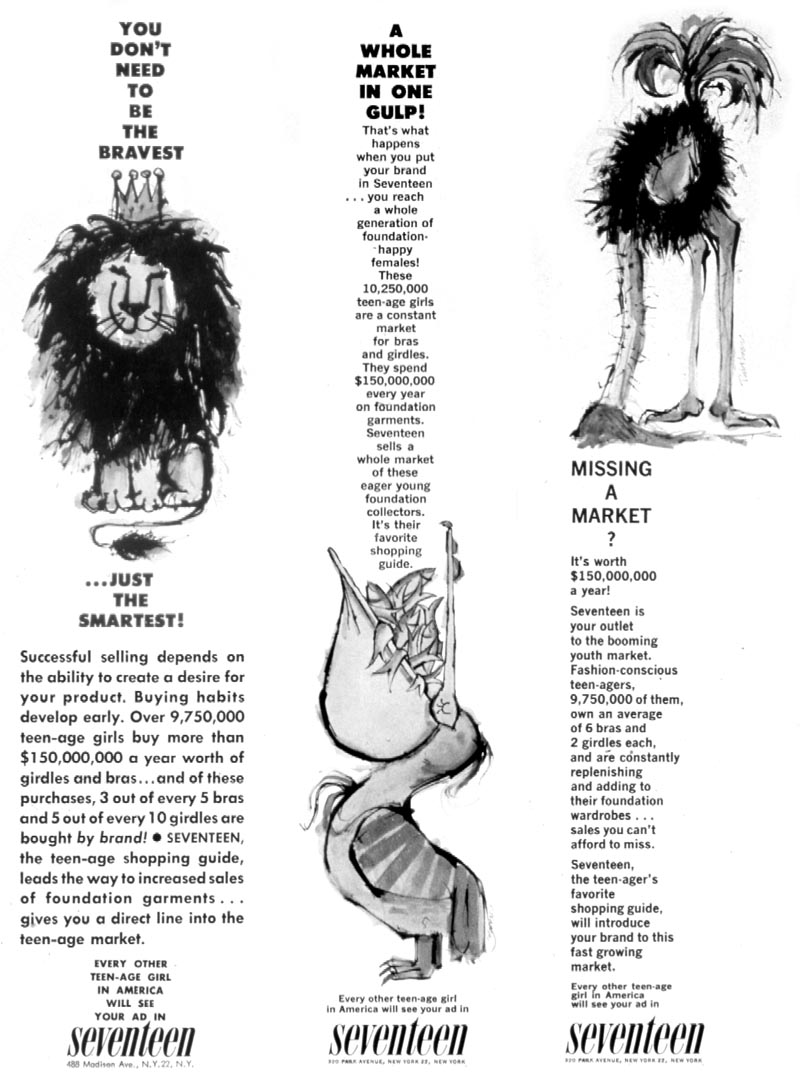

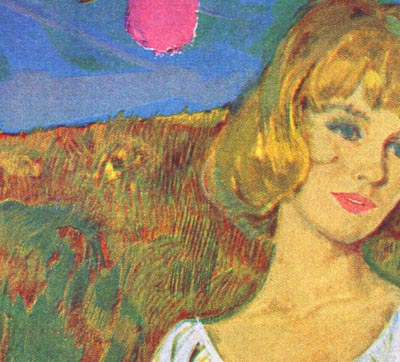

All these examples, taken from the first two decades of Tinkelman's career, suggest that the restless illustrator rarely settled twice on the same visual solution to any given problem.

That is to say, Tinkelman took the notion that success could result only from working in one style and turned it on its head.

But, some might protest, wouldn't art directors shy away from an illustrator working in so many styles, fearing that they might get unpredictable results when he delivered his assignments?

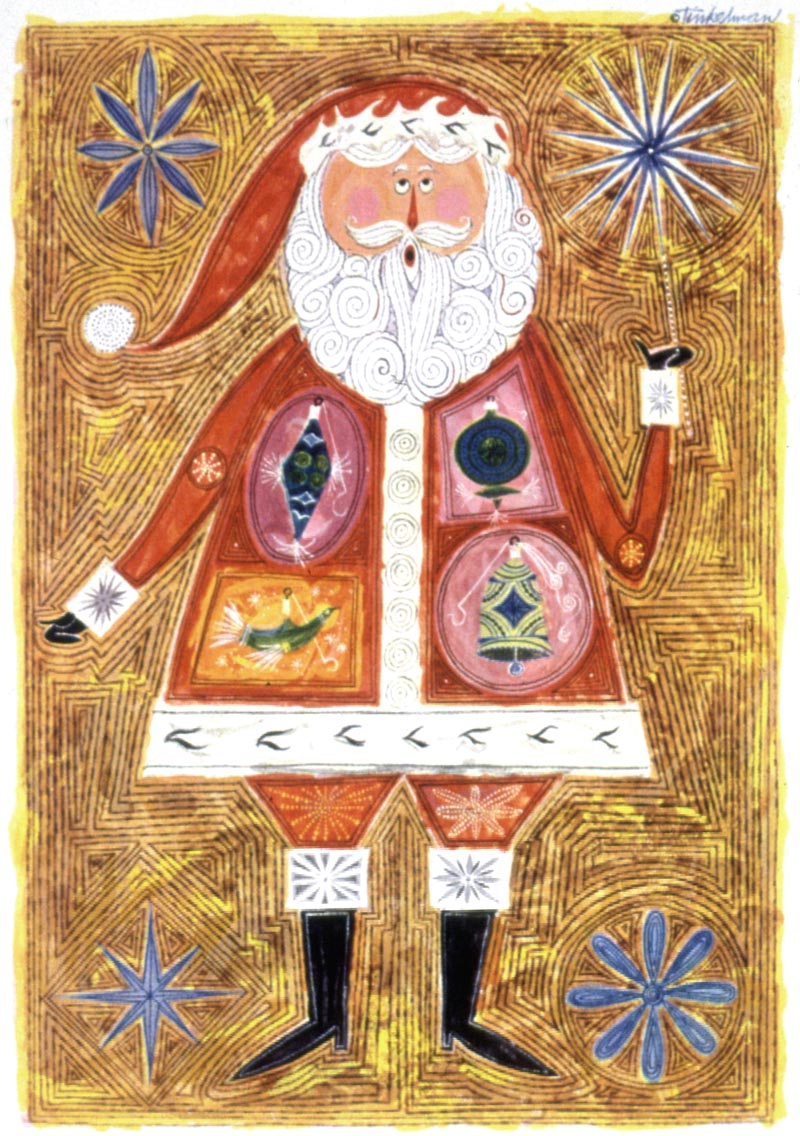

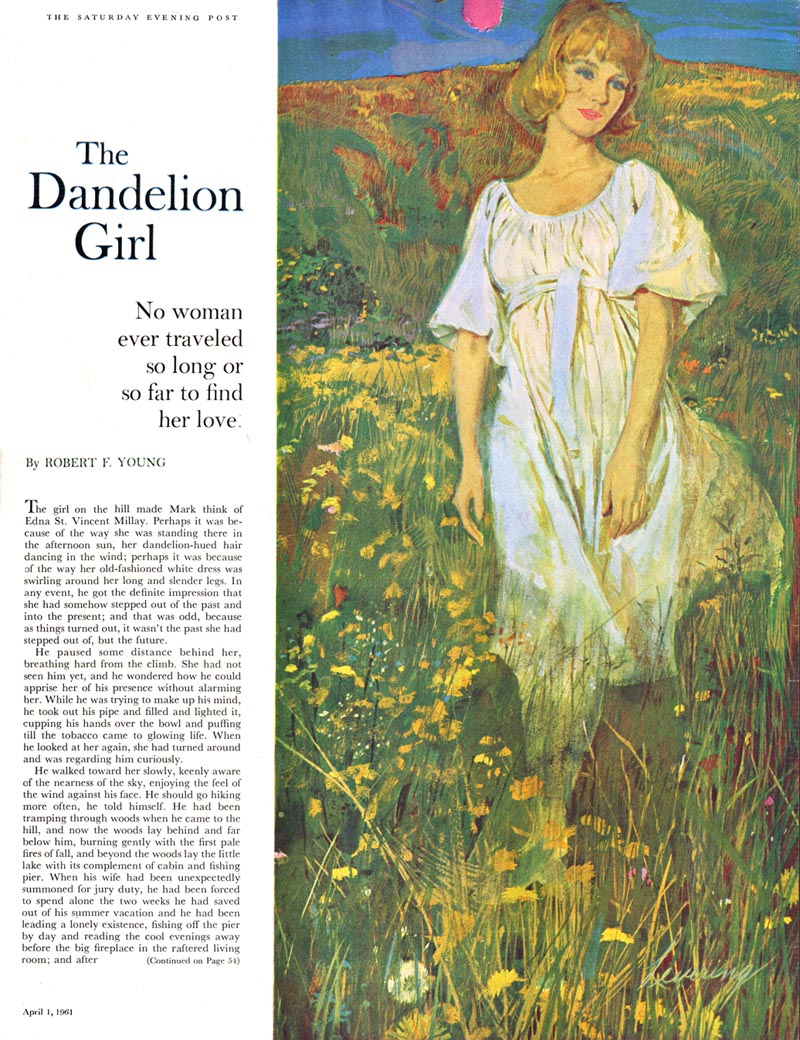

In fact by the time Murray Tinkelman discovered what would become his 'signature style' (below) he had already won a gold certificate and twenty-seven certificates of merit from the Society of Illustrators and an award of merit from the New York Art Directors' Club (among many others) through his stylistic explorations.

"I enjoy variety and I try to use style in the same way a typographer uses type faces," said Tinkelman in a 1970 interview in American Artist magazine. "The style is not dictated by whim, nor by the art director, but by the problem the job presents."

Looking back on the early days of his career, Murray Tinkelman told the American Artistinterviewer, "... the role of the illustrator is changing from a descriptive one to an interpretive one. The illustration used to be redundant, really, because it was all taken directly from the text. Nowadays the artist helps tell the story, rather than just echoing the author's words."

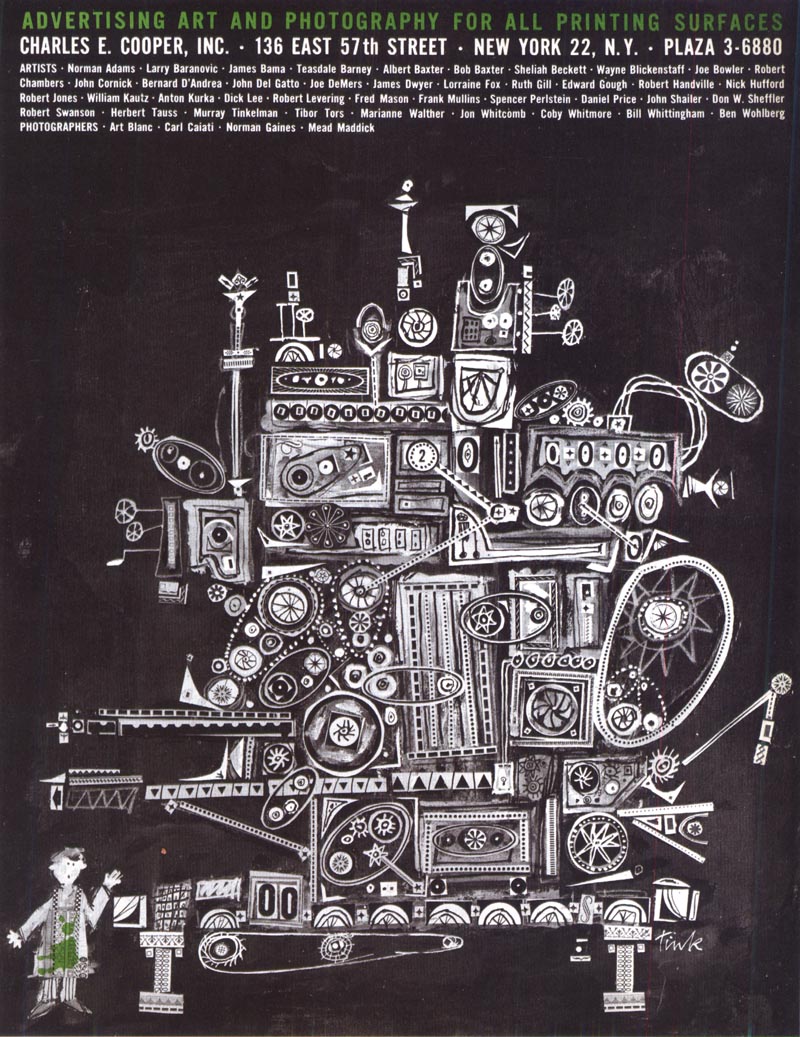

Murray joined the Charles E. Cooper Studio in 1958. "The salesmen," says Murray, "the first two years, never had any confidence that my stuff was salable. It was infuriating."

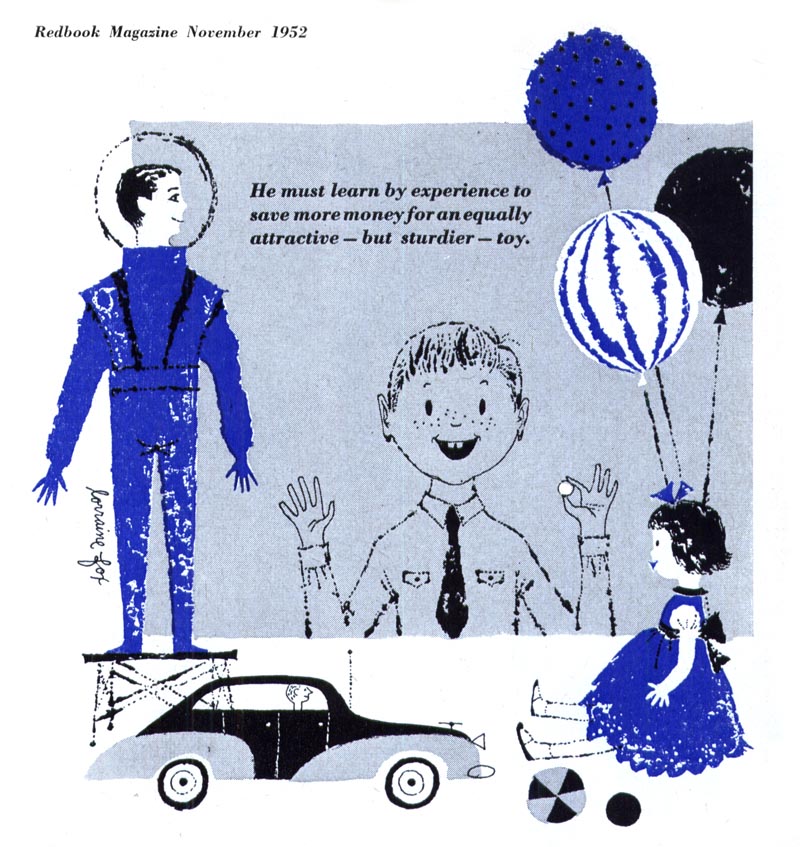

In spite of the hurdles ( Murray made only $1,800 that first year at Cooper's ) he was gaining something more valuable than money: "I was very young, and my relationship with (Coby) Whitmore, (Joe) Bowler, (Joe) DeMers, and Lorraine Fox and Bernie D'Andrea... being mentored by those wonderful narrative illustrators... meant the world to me."

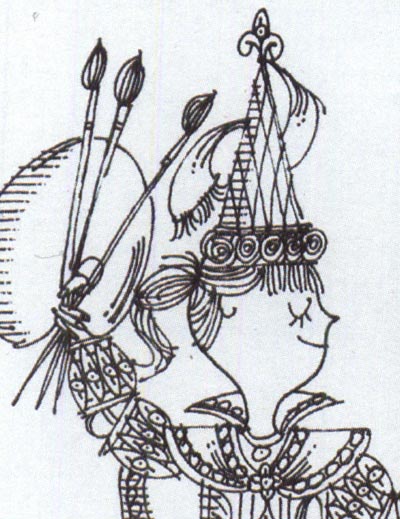

"My proclivity was in a much more decorative style."

Cooper's salesmen may not have known what to make of Murray Tinkelman, but Chuck Cooper himself must have had a sense that times were changing. Perhaps that's why he decided to take a chance on the kid with the oddball style who had wandered in for an interview from his dead-end job at a third-rate greeting card company. At the time not even Murray could have anticipated what he would accomplish.

But this colour-blind kid from a poor part of town was going to surprise everyone.

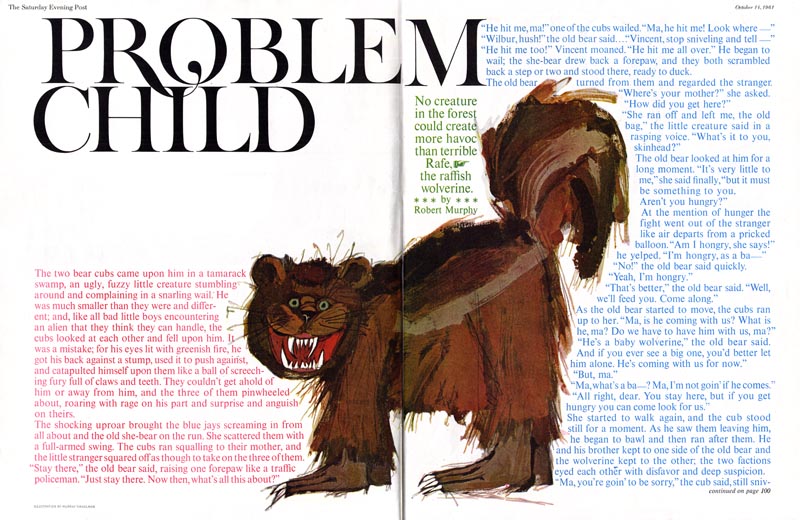

Problem Child

If Mrs Goodheart were alive today, she would probably be surprised to hear that Murray Tinkelman grew up to become an award-winning illustrator, educator and illustration historian. In the early 1940's, when Mrs. Goodheart was assistant principal at Murray's junior high, she advised his parents to send the boy to the High School of Industrial Arts -- otherwise he might end up in jail.

"I was just a hideous student," says Murray as he recalls his childhood, "I was terrible in all my academic subjects and the only thing I had any ability in was drawing."

"I lived in a huge apartment house in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. There were a hundred and eleven families on six floors. During World War Two there were these paper drives and people would deposit their newspapers and magazines in the incinerator rooms. A maintenance man would come around and collect them for the war effort. My father was a radical progressive, so we were never allowed to see the Journal Americanin our home - but they had all the great comics - so I used to guiltily take out Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon from the papers left in the incinerator room and take them into my room and hide them."

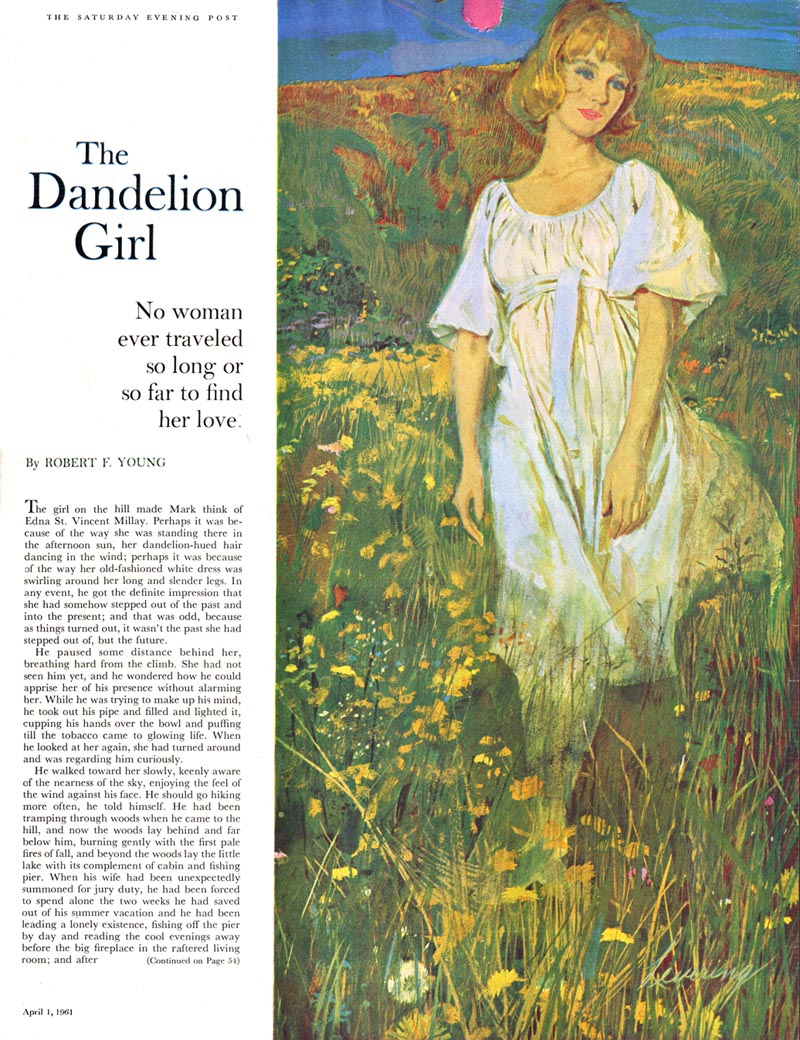

"The same thing with the Saturday Evening Post, which my father thought was antisemitic. But I loved the Post, so I'd tear off the covers and some of the interiors and hide those, too."

Murray would study the drawings of Alex Raymond and Hal Foster and try to copy them in his own drawings. "Even the way Prince Valiant was lettered," he adds.

He knew about Superman and Batman, but "comic books were a dime and there was no money in my family (or very little) so comic books were a real rarity for me." Which is ironic, because Murray's first job was working in a comic book art studio.

"I had just graduated from high school," Murray explains, "and my best friend in high school was Dick Giordano. He got a job at Iger Studios. We both interviewed the same day, but Dick was so much better than I was he got the job that same day. About three months later, I got a call to show up. I started at the same lowly job that Dick had started at, making thirty dollars a week, doing 'clean-up'. I would erase the pencil lines on the finished inked pages and I would rule the lines around the panels. And then I kind of graduated after about three weeks to doing backgrounds. And then after a while I graduated to doing figures. But no heads! One guy who was the shop 'boss' (Al something-or-other) did all the heads... male, female... and they all looked alike!"

"But I was really awful... I was not very good... and I was fired. We worked from 8:30 to 4:30 and I got called down at 4:15 and I knew I was going to be fired. I had come in about 30 seconds late that morning and (Jerry) Iger was at the door, and he looked at his wristwatch. I said, "Are you checking your pulse?" But it wasn't because of that, it was because I really wasn't very good. So around 4:15 he called me down... I had already said goodbye to everybody. I cleaned my brushes and said, "I'll meet you at the bar around the corner." So he called me down and he said, "Well, we're a little slow..." and I said, "We're not slow, everybody's busy here." I just wouldn't go down quietly. My mother always said I had a big mouth."

"Iger said, "If you don't watch your mouth, we won't call you back" and I said, "Well, I'm not coming back anyway." and I left in a huff. I went down to the bar and ordered a beer and the entire staff came down to say goodbye to me. I didn't know what the future would hold, but I did know that I was going to join the Army, and get that out of the way."

"It was the Korean War and many of my friends had already been drafted. I didn't really like the idea of getting shot at, and I had heard that the Army would accept a two-year enlistee, so I figured maybe it was better to get in and get out early."

Murray spent his first year in the Army doing art work for training aids and posters. The second year he decorated cakes and painted "Welcome to Germany" signs for newly-arrived wives of officers. He even decorated cigar bands for officers whose wives had had babies.

When he returned to civilian life he attended Cooper Union in the evenings while working days at a series "dull paste-up jobs".

Murray says, "I went from the Army to Norcross Greeting Cards. I remember it was my first job out of the Army because my mouth was filthy with 'barracks talk'. I was the only male in the department and I was so embarrased because I would just say "Fuck you" - it was just automatic... even at home I would say "pass the fucking salt"... it was awful... I lasted about three months there. I got the lowest level job, called 'scaling'. Each day or so we would get a stack of finished comp art, same size as it would eventually be reproduced. And our job was to put it in a Lucie and blow it up to half-up, and then do a precise tracing of that finished art. We'd give that to the boss of the scaling group, who would give it back to the original artist, who would then do an actual piece of finished art which would be reduced by 1/3 for printing so everything would 'tighten up'. "

Murray left Norcross for American Artists Group, another greeting card company. He had managed to sell Norcross a few actual illustrations on a freelance basis and hoped to do the same at AAG. "I was making maybe $35 a week at this point," says Murray, "So I left American Artists for yet another greeting card company, Wallace Brown..."

"... and at Wallace Brown I was making $50 a week -- but I was doing very, very well selling them groups of greeting cards for boxed sets, which would involve 12 to 24 individual paintings. I would look at what was being done and think, "well, if its good enough for Hallmark, its good enough for me." So I would do boxed sets of Christmas cards or boxed sets of Valentine cards.

And I was clinically depressed by the junk I was doing!"

The Charles E. Cooper Studio

"I was working staff at Wallace Brown Greeting Cards and my wife was pregnant. I was home and I was so, like, clinically depressed by the mechanicals and the colour separations and the hideous work I was doing at Wallace Brown. I literally could not show up at work. So I called in sick."

That day became a turning point in Murray Tinkelman's career. In an interview with TI list member Neil Shapiro published in Illustration Magazine #18, Murray described what happened next:

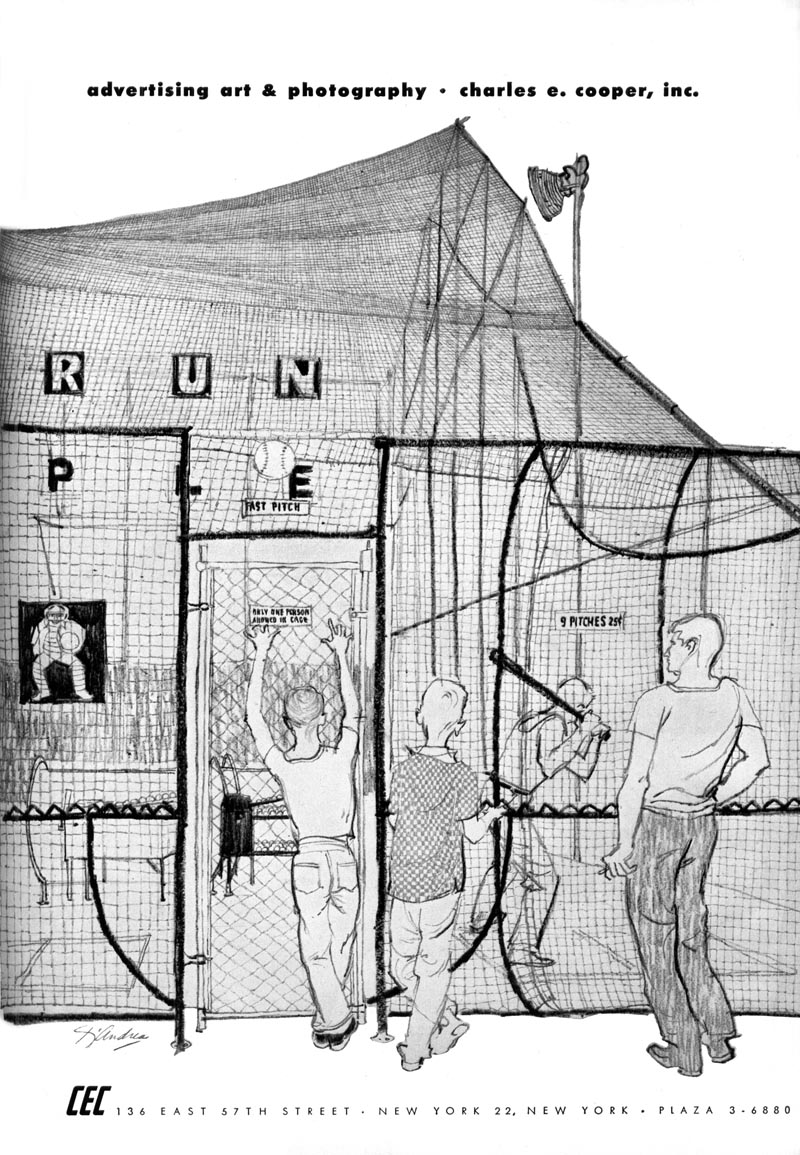

"I was looking through [the 1956 Art Directors Annual]. I came across a stopper -- an absolutely beautiful pencil drawing of some people leaning up against a wire mesh fence looking in at a baseball batting situation. It was a marvelous drawing - beautifully composed, beautifully drawn with a modern flair to it."

"I noticed that it was an advertisment for the Charles E. Cooper Studios. I'd never heard of Cooper Studios. I did not know the name Bernie D'Andrea, which was the name on the drawing that attracted my attention. So I called Charles E. Cooper studios to make an appointment to show some samples."

It was an interview that almost didn't happen. That Thursday in the reception area at Cooper Studios while waiting for his turn to be meet with Chuck Cooper, Murray got cold feet. "But," he says, "I couldn't get out of there fast enough and they called my name before the elevator came."

"Chuck had this gorgeous corner office on the ninth floor in this building on the corner of Lexington and 57th St with windows on two sides... it was just this gorgeous, light-filled office with indirect lighting and copper-leaf walls. And he looked through this terrible portfolio I had brought."

Based on what he had seen while fretting in the reception area, Murray's interview with Cooper was not what he had been expecting.

The artists who had interviewed before him seem to have been in and out again in about thirty seconds each. By comparison, Chuck Cooper devoted an inordinate amount of time to Murray's portfolio. He carefully examined each piece, then turned it over and stacked it carefully in a pile. Then he turned over the pile and examined each piece again. When he was at last finished Cooper looked up at Murray and said, "All right, be here Monday."

Murray says, "I accepted the position at Cooper, and I had no idea I was now completely freelance - and with no income."

"The next day I showed up at Wallace Brown and I said to the art director that I was going to have to leave. Immediately. Because I had been hired by Cooper Studio. And he was so relieved because he liked me. He had heard of Cooper and he had nothing but admiration for it so he said, "Terrific - good for you - go with God!" He didn't try to keep me at all because I was awful!"

"So I went home and I said to Carol, "I quit my job." Here she's pregnant, we had no money in the bank... she said, "You what?!"

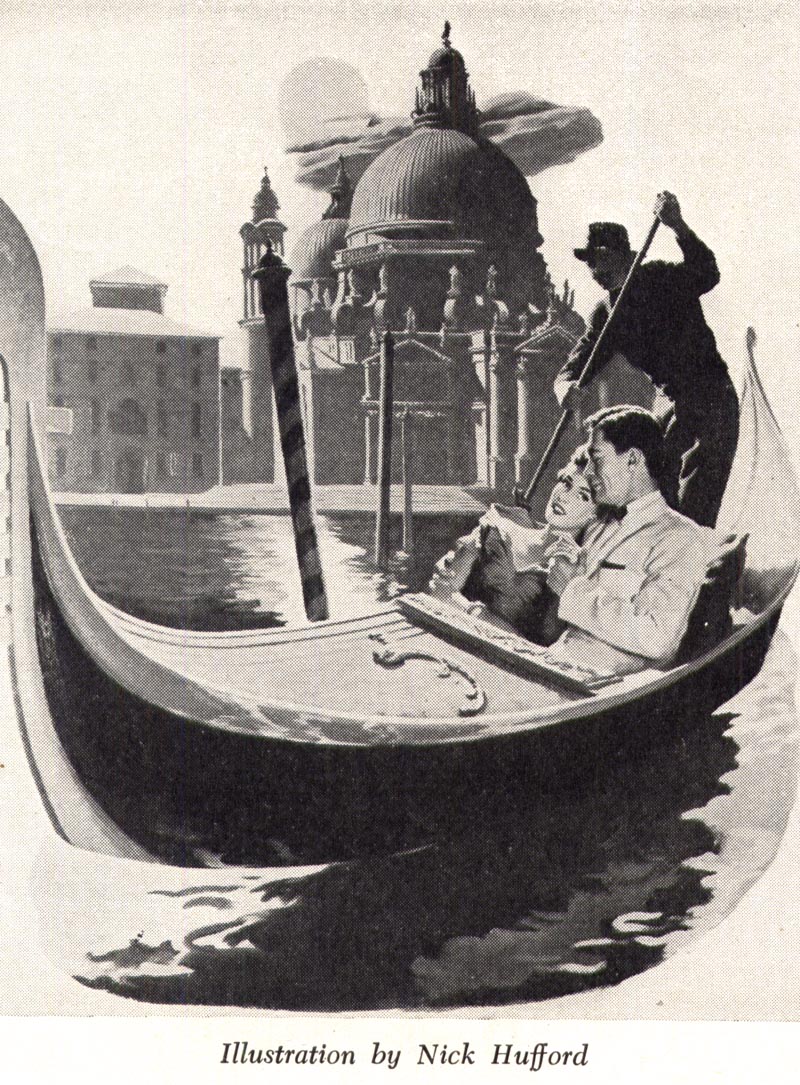

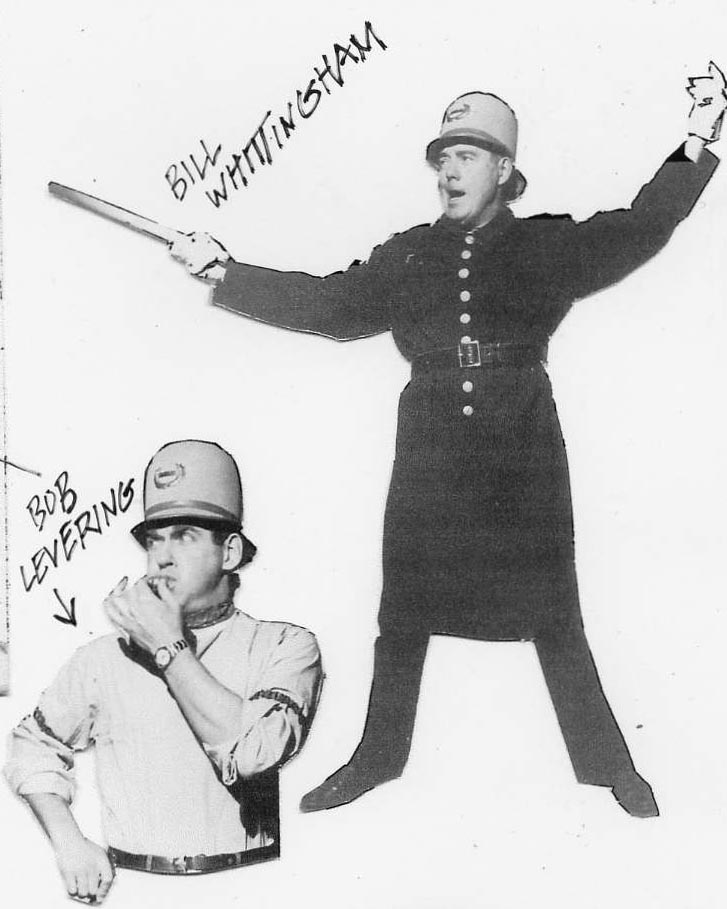

"So Monday morning I show up at Cooper Studio. There were two full floors, the 9th and the 10th floor. They had one suite of offices on the 11th floor that had broken Lucies and busted furniture... a couple of old Steven Dohanas tabourets... it was a shambles. And that's where they put me. And I shared that space with Bill Whittingham, who's now a portrait painter (he was Joe Bowler's heir apparent) and Nick Hufford, who was originally an apprentice to Haddon Sundblom..."

"...and a thorough alcoholic and maybe the funniest man I ever met in my life - Nick was insanely funny."

"So we'd go down to the bullpen to get art supplies, and I'd get introduced around by Bill Whittingham. The first person he introduced me to was Bob Levering (who was and is the sweetest man in the world). Levering became instantly supportive of me."

That first year as a Cooper freelancer was incredibly demoralizing for Murray. He told me about his first job for the studio:

"There were about five salesmen at Cooper", he explains, "and one of them brings back this job. I took a shot at it and he couldn't understand it and he didn't even like it. He gave it to another artist, Bob Swanson, to redo. Bob did a pretty competent job," he chuckles. "It went through, but they never even showed mine."

"Finally after maybe two months of this, I went into Chuck's office and told him, "Hey, I gotta leave. I'm starving to death here. Bills are piling up... we're about to have a baby..."

"And Chuck said, "How much do you need -- to live?" So I said, "Well, at least ninety dollars a week (which was ridiculous... it was just a figure that jumped into my head, it was way too low)." So he said, "All right, I'll put you on a ninety dollar a week 'draw'. A 'draw' was a payment against income I was supposed to generate for the studio.... except I didn't generate any income! So I'm going deeper and deeper in the hole... and Chuck never, ever said, "Where's the money... when are you gonna pay me" ... nothing like that. At all. There's gotta be a heaven ... for Chuck."

Murray has often spoken about his great affection for Lorraine Fox and his admiration for her work. He has gone so far as to say "Lorraine Fox was my hero". But when he first met her during his early days at Cooper he was surprised to discover that they were not exactly on the same page:

"Lorraine was a very quiet, very reserved lady. And underline lady. She was a Lady. Very elegant, a very handsome woman... "

"...and I was... disappointed by her lack of response to what I was doing. I was in the bullpen getting something matted. And Lorraine came in and she was getting something matted before she delivered it. She didn't say my work was crap or anything, but she just looked a little cool about it."

"And I mentioned it to one of the other illustrators, Don Crowley, and he said, "Don't worry about it. Lorraine has her own goody factory and maybe she just doesn't understand."

"What I was doing at that time was pretty rough. It had touches of abstract expressionism... 'gallery painting'... pretty sloppy stuff."

"I was kind of disappointed that Lorraine wasn't more responsive to what I did (and neither was her husband, Bernie D'Andrea - he looked at me like I had two heads). But Bob Levering, and through Levering, Joe Bowler and Coby Whitmore and Joe DeMers became my support system."

I asked Murray to decribe his first really big, well-paying job at Cooper's:

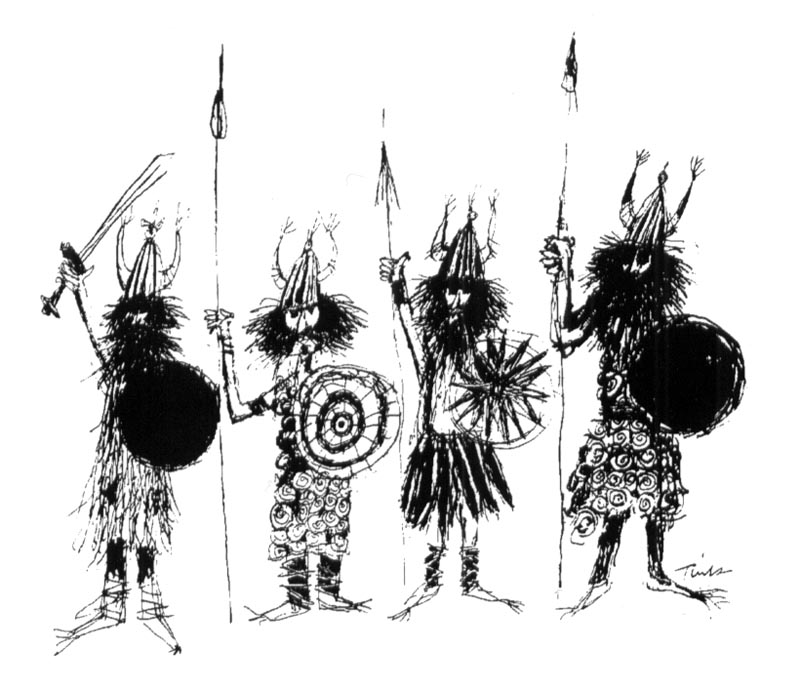

"One of the salesmen came in with a job from the Grollier's Society. They were publishing an encyclopedia for high school kids. And I got $1,800 for that one job, which was as much as I had made the entire previous year. They were these very ragged drawings... kind of an expressionistic pen-and-ink style."

"It was great! I got cocky immediately... maybe on the edge of insufferable. I mean, here I am, a big-shot now, and starting to make some money for Cooper."

"That was a break-through. I don't think I was ever in the red again after that job... there was always something on the board, there was always a cheque in the mail."

"Fast forward for a minute here: there was a point in 1961, when I did my first Saturday Evening Post job. And it was a thousand dollars for one painting. And I went into Chuck's office and I gave him a cheque for five hundred dollars. Now Chuck did not take any money from editorial jobs -- he only took money from advertising -- and this was an editorial job. He said, "What are you doing?" and I said, "Well, you staked me to that draw." And he said, "Well can you afford this?" And I remember saying ,"I can't afford notto do this." So he took the cheque - reluctantly."

Murray chuckles, "He said I'm the only person in the history of the Cooper Studio who paid back money from a draw."

"The One-Man Pushpin Studios"

In Illustration Magazine # 18, Murray Tinkelman told interviewer Dan Zimmer, "I had really distinctly different styles for periods of time. I was the second best Lorraine Fox in New York City. And I could do an adequate Milton Glaser. I was a one-man Push Pin Studio." I asked Murray to elaborate on those early influences and explain how they helped shape his style....

Murray begins... "The Push Pin guys graduated from Cooper Union in 1951... and they used this place in Manhattan, Harry Lapow, a package design studio, as a kind of 'maildrop' - a headquarters. Before the Cooper Studio I got a staff job there for a couple of weeks - for peanuts - and I was fired from there as well," he chuckles. "I was doing mechanicals and they tried me out for design stuff and I was awful (I didn't think I was that awful, but they did) and I think that's where I became aware of Push Pin. Because of their relationship with this Harry Lapow I came across a Push Pin Almanac - the original publication - and I just loved their stuff. I still think Milton Glaser is a brilliant illustrator/designer - and person."

For Murray, the discovery of the Push Pin artists was a revelation. Murray told me, "I've said before that I only had three problems with becoming an illustrator: I couldn't draw, I couldn't paint and I was colour-blind. I had no training... I never had an illustration course in my life... I only had one semester of figure drawing... I really felt unencumbered by knowledge!"

Murray had already become aware of Lorraine Fox's work when he was employed at American Artist Group Greeting Cards. He says, "[In spite of having no formal illustration education] I knew enough that what Lorraine was doing was brilliant. Anybody could tell what Al Parker did and what Norman Rockwell did was brilliant. But Lorraine was doing brilliant stuff that didn't depend on the academic foundation of Parker or Rockwell."

"So it wasn't that far a stretch to see how smart and how talented Milton Glaser was. In a way, he lived in that world that Lorraine lived in... that world of decorative illustration. It wasn't quite cartooning, it wasn't quite narrative illustration, it was a kind of symbolic illustration that depended on folk art as a root source."

One of my pen-and-ink styles was strongly influenced by Milton Glaser (and then later a combination of Glaser and John Alcorn).

I asked Murray if he felt his work during this period was his own or if he was simply following a trend.

He replied enthusiastically, "Great question - and I've thought about this and I think about it in my relation with my students. I really did believe it was me and it was personal. And no more or less personal than when I moved to abstract expressionism, or no more or less than now when I'm working in photo-realism. I think they're all evolutionary stages - and I think they're all me."

"I can tell you this with utmost sincerity: I never once did a job that I didn't believe in - at least when I did it."

He laughs, "I also liked everything that I did - or else I wouldn't have let it out of the studio!"

The Magic of Intersecting Lines

Each life is like a line put down on a blank sheet of paper. Some are arrestingly brief and others surprisingly long... some are arrow-straight while others are convoluted.

A line on its own can certainly create an interesting picture... but it is usually at the point where lines intersect that something special begins to happen.

Lines have played an important role in Murray Tinkelman's life. And at the multitude of intersecting points where Murray's lines have criss-crossed...

... something magical has happened!

In a 1970 article in American Artist, Murray talks about how important Arnold Burgess, one of his teachers at the High School of Industrial Art in New York, was in shaping his young life. Mr. Burgess saw potential in young Murray Tinkelman, took him off the regular course of study and gave him free reign to pursue his own artistic interests. Murray subsequently won his first award, the High School Portfolio Award, and received his first professional assignment - a small spot that was used as a column header in Seventeenmagazine.

Imagine if Murray's and Mr. Burgess' lines had never crossed.

Fast forward a few years... after leaving the Army, Murray received the Max Beckman Painting Scholarship, which gave him the opportunity to study at the Brooklyn Museum Art School with Reuben Tam (below).

Learning from Tam "truly changed my life," says Murray. He describes Tam as "sensitive, thoughtful, [the] greatest teacher, [a] brilliant painter, [a] wonderful man." Would Murray Tinkelman be the same person he is today had his and Tam's paths never crossed?

Next came Chuck Cooper, owner of the preeminent art studio in America. The intersection of lines that resulted in Murray being accepted into the Cooper Studio are marvelous to behold: a chance sighting of the D'Andrea drawing in the '56 Art Director's Annual, an interview almost aborted save for a slow elevator and a speedy call to enter, a studio head who, having already turned away a dozen others that day, saw ... something - some potential - in this kid from Brooklyn with the ragtag portfolio.

At Cooper's the intersecting of lines really got exciting! The youngest member of the Charles E. Cooper studio began luring ("like a pied piper", is how Murray describes it) his fellow illustrators away to visit the Brooklyn Museum and Reuben Tam's class. (Another piece by Tam below)

First to go with Murray were his early supporters, Bill Whittingham and Bob Levering.

Then they dragged a less-than-enthusiastic Bernie D'Andrea along (Murray still laughs as he quotes D'Andrea's initial reaction: "Aaahh, what a buncha shit!")

Gradually, one by one, others like Coby Whitmore, Joe DeMers and Lorraine Fox began visiting Tam's class. Consider that the Cooper artists were rightfully regarded by both peers and clients as the crème de la crème of American illustration of the day. Certainly there were many other important factors that would have affected the Cooper group to explore outside their comfort zone. Still (and Murray himself would protest) his role in influencing the thinking and styles of some of the most important illustrators of the 50's should not be discounted. In Neil Shapiro's article in Illustration Magazine # 16, Cooper artist Don Crowley described Murray's influence (somewhat facetiously) on the Cooper staff as "[getting] those guys dissatisfied with what they were doing... they weren't happy doing illustrations any more. They wanted to be fine artists."

Murray has often praised the Cooper artists for being his mentors during the early days of his career -- but in a sense, he was also mentoring them. He told Neil Shapiro, "I don't think my work as an illustrator really affected them, but it was my role as a representative of the next generation." Had Murray Tinkelman never been there to gently nudge the Cooper artists in Reuben Tam's direction, one has to wonder how things might have turned out differently for everyone of them...

One day, 20 years into his career, the intersection of lines took on an even greater importance for Murray.

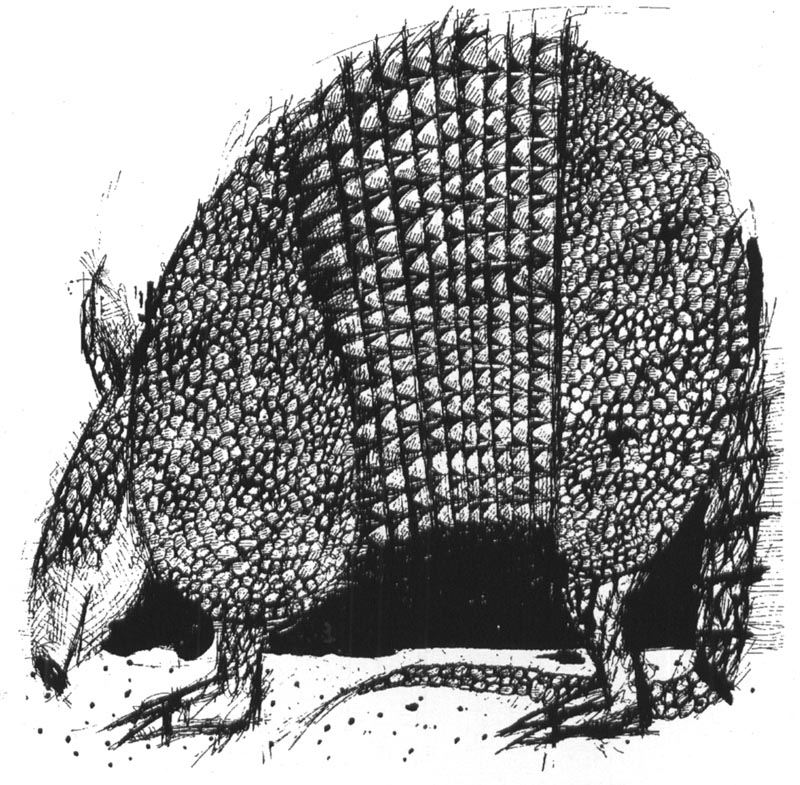

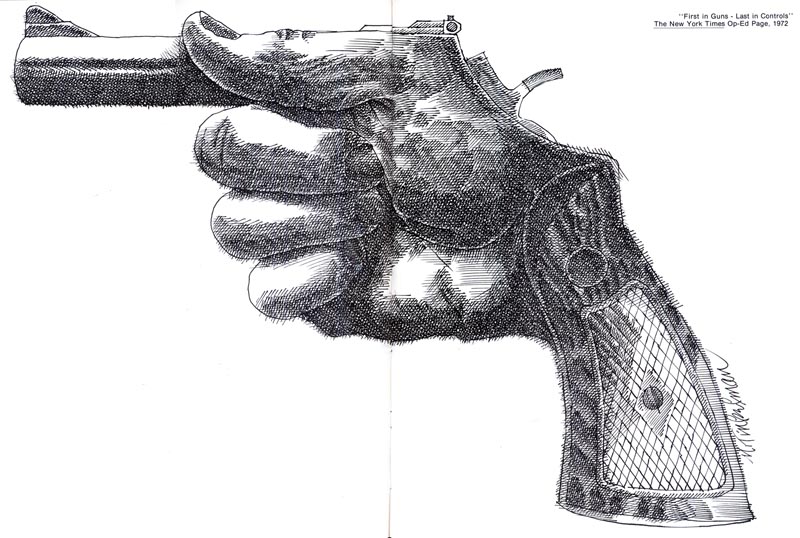

"I was doing a little bit of everything," he told Dan Zimmer in an interview in Illustration #23, "I hadn't really settled on what would be called a 'signature style'... then one day I was drawing abstractly in a sketchpad, and I was messing around with crosshatching, a landscape of crosshatching, just stream-of-consciousness stuff. Then I looked at a photograph of a rhinoceros, and I started doing a cross-hatched drawing of the rhino in the same technique, without the abstraction. And it won a gold medal at the Society of Illustrators!"

"By 1970, I had pretty much crystalized my current technique."

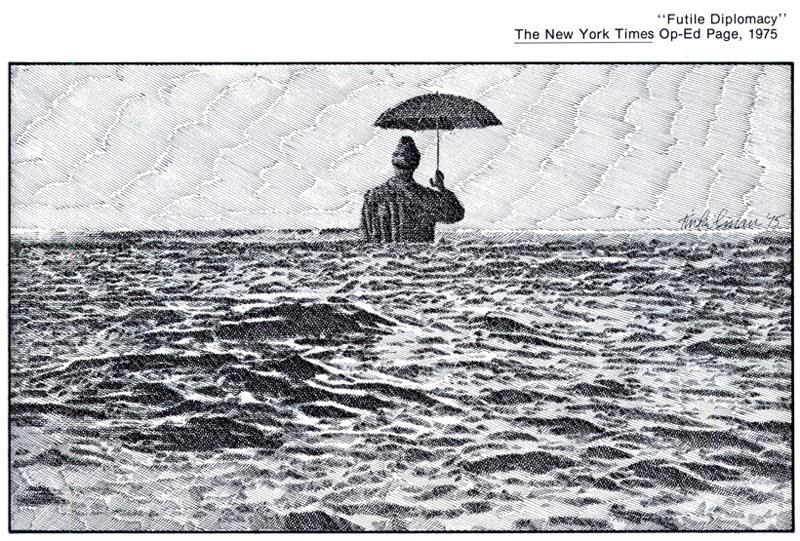

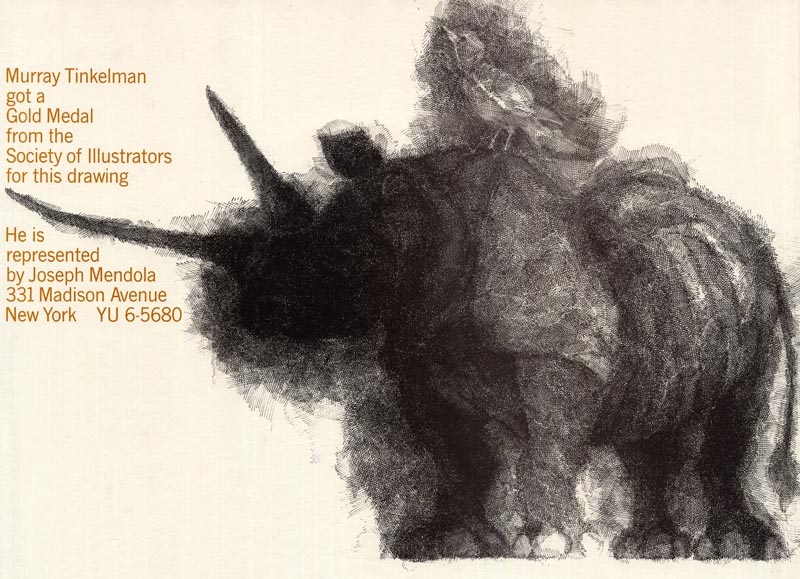

For Murray, the floodgates had opened. He began receiving assignments from the New York Times op-ed page...

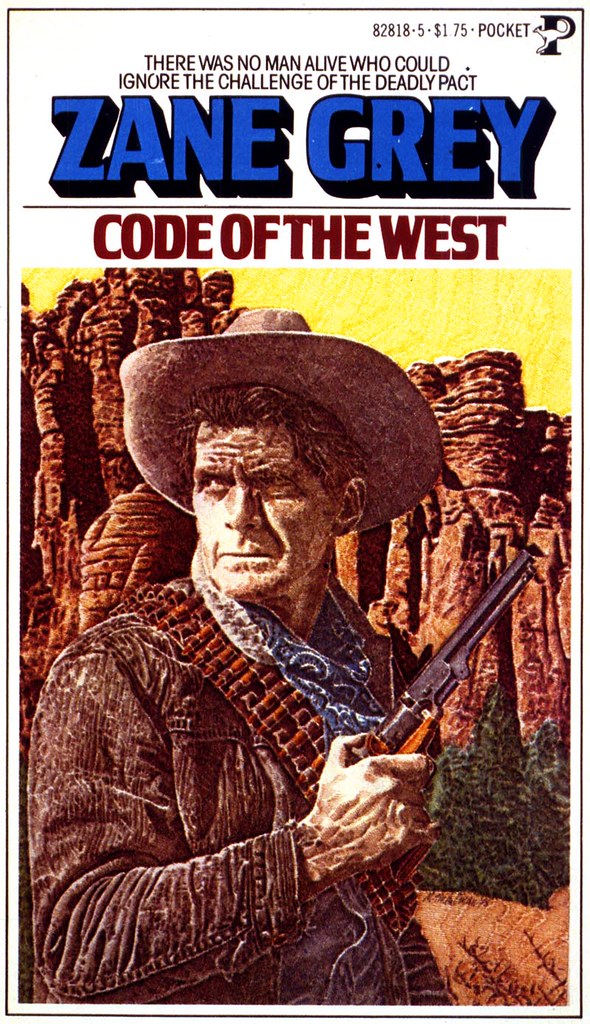

...he did a memorable series of H.P. Lovecraft book covers -- a western-themed sample that crossed the path of the president at Pocket Books lead to a series of 45 Zane Grey covers...

By the 1980's, says Murray, "I got nervous if the phone DID ring, because I didn't want to do the jobs." He began focusing more on personal projects - enjoying the opportunity to explore subject matter that interested him - cowboys and indians, airplanes, baseball - thanks to the freedom afforded by his income from teaching.

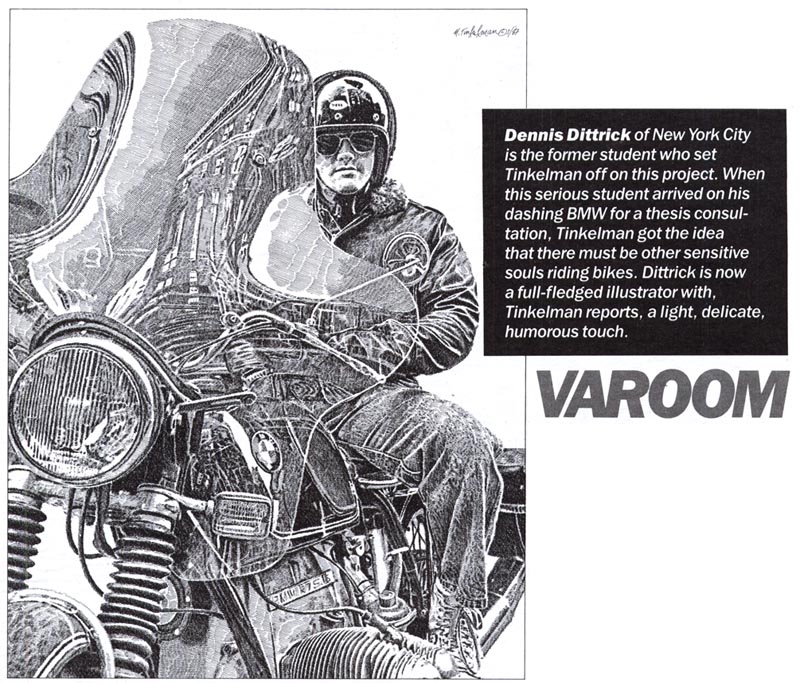

Far longer than his time as a student of Burgess, Tam and the Cooper staff, Murray has been a teacher of illustrators-in-waiting. Eleven-and-a-half years at Parsons... 27 years at Syracuse... 4 years and counting at Hartford.

The connections he has created for others in his many years as an educator far outweigh all the countless intersecting points in the thousands of cross-hatched illustrations of Murray Tinkelman's career. Murray initiated the teaching of the history of illustration at Parsons back in 1965, and as he says, "now its all over the place." In 1999 the Society of Illustrators presented him with The Distinguished Educator in the Arts award.

This perhaps is Murray Tinkelman's greatest masterpiece: he has drawn the lines connecting one generation of illustrators to another.

When Murray Tinkelman drew those lines, he drew magic.

Many thanks to Murray Tinkelman for the time and trouble he went to in providing me with visual and written material for this series. Thanks also to friends Neil Shapiro for his insight and assistance, René Milot for scanning Murray's slides, and Mark Korsak for providing additional scans.

Some important related links:

Illustration magazine #16, 18, and 23, where you'll find much more extensive information and discussions about and with Murray by Neil Shapiro and Dan Zimmer.

Addendum: Lunch with Murray

... and Mitchell Hooks all have in common? Well, for starters, they are all fabulous illustrators who got their start in New York during the mid-20th century. I can tell you something else they have in common; they are all wonderful, gracious gentlemen with whom anyone would be fortunate to spend some time.

Say, over lunch.

So what do Murray Tinkelman, Bob Levering and Mitchell Hooks all have in common with me? Well, about two weeks ago - on my birthday - the four of us were sharing a table in the dining room of the Society of Illustrators in New York City... having lunch.

To say I was thrilled beyond belief would be an understatement!

I never imagined I'd ever even set foot in the door of the Society and yet here I was - as Murray's invited guest - eating, drinking and sharing stories with three of my idols. Hanging on the wall just inches from my head, a gorgeous original by N.C. Wyeth - and lining the walls all around this bright, inviting room; original artworks by so many of the giants of the golden age of illustration.

Some twenty feet away, hanging over the bar, a magnificent original by Norman Rockwell. "Its probably worth more than the entire building," Murray said to me in an aside as I gawked in amazement. I'm still not sure but I suspect he was only half joking.

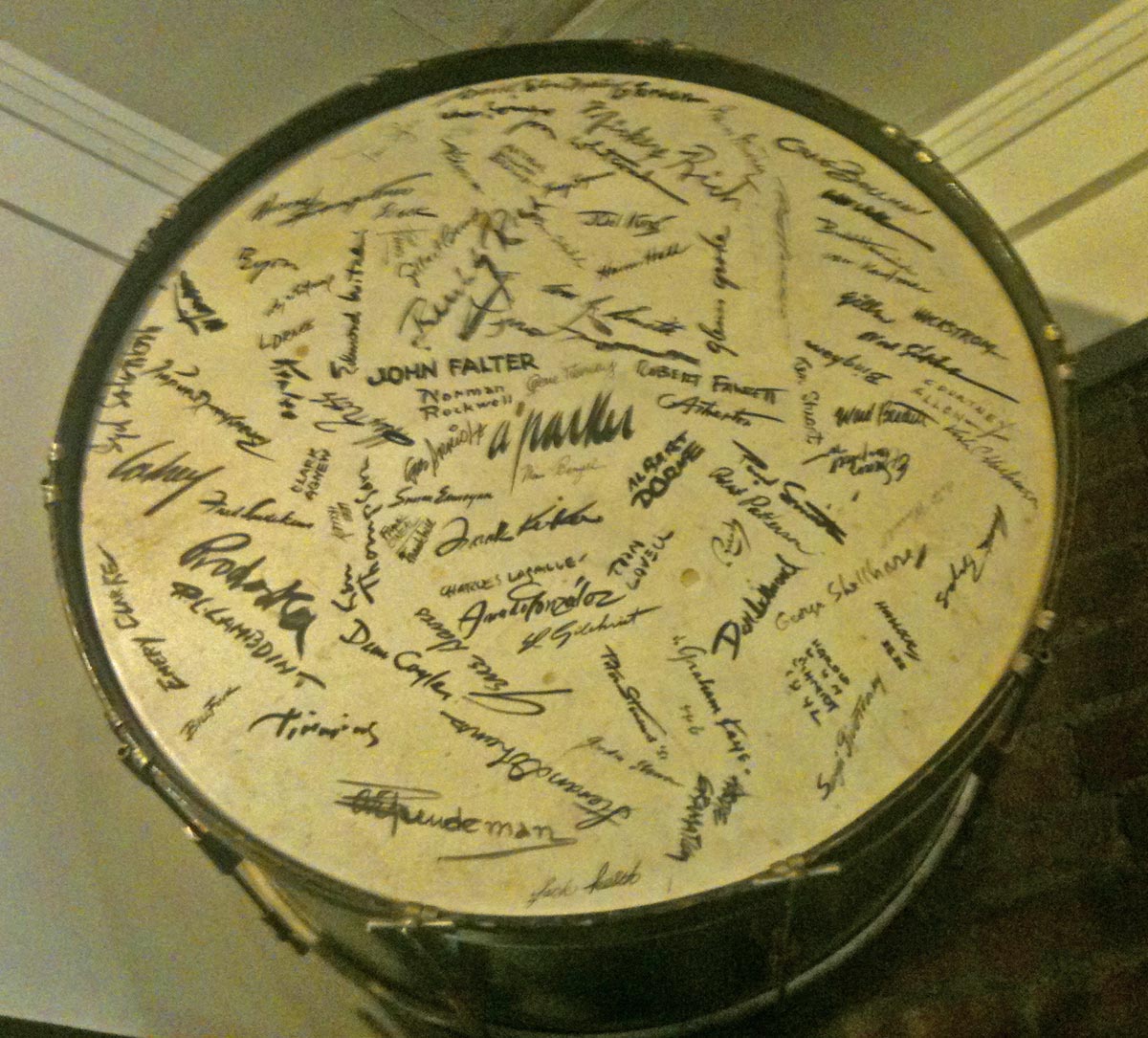

Hanging near the ceiling in another part of the room, Al Parker's drum, signed by his many illustrator friends and associates. "Make sure you get a picture of that," advised Murray. So I did.

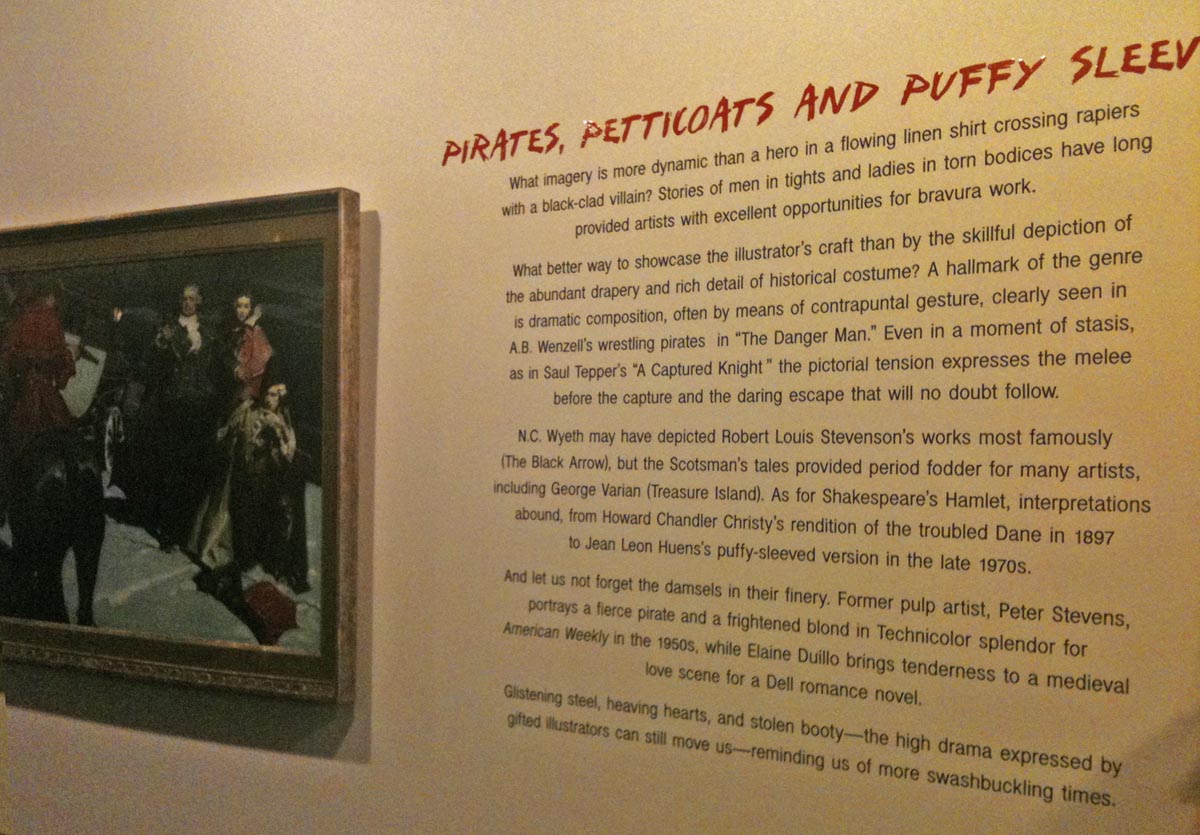

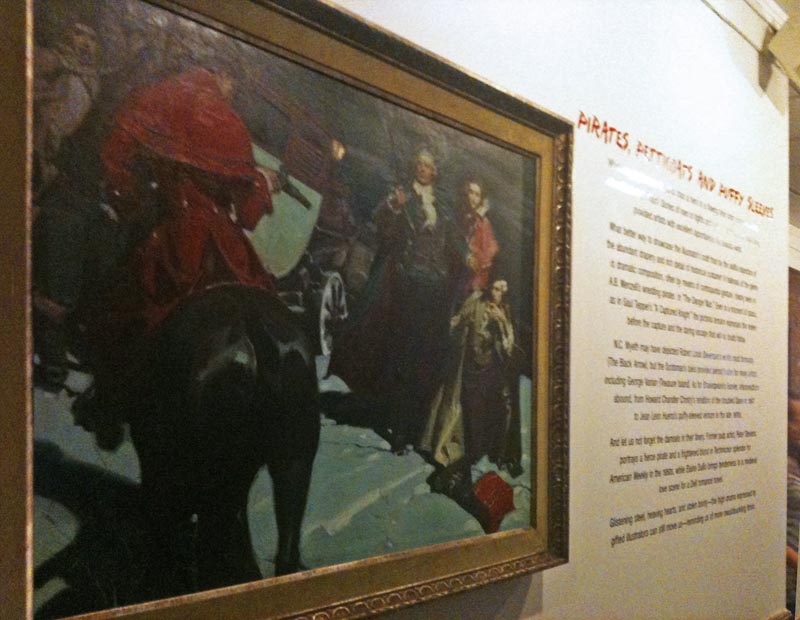

The show currently on display in the Society dining room is called "Pirates, Petticoats and Puffy Sleeves" and if you are in a position to go see it I promise you will come away feeling awestruck.

This magnificent Saul Tepper is a fitting introduction to the show, but I bet that, like me, you'll find yourself captivated by each and every piece you stand in front of as you make your way around the room. Murray and I toured the show together and all I could say was "wow... wow... wow..." as we stopped and admired each glorious piece. Its great to know that so many beautiful works of art have been saved - after all these years - and are secure and well cared for in the best possible home they could have. It was fantastic to see that the good people at the Society of Illustrators bring these treasures out into the light of day so a new generation can admire and learn from and be inspired by them.

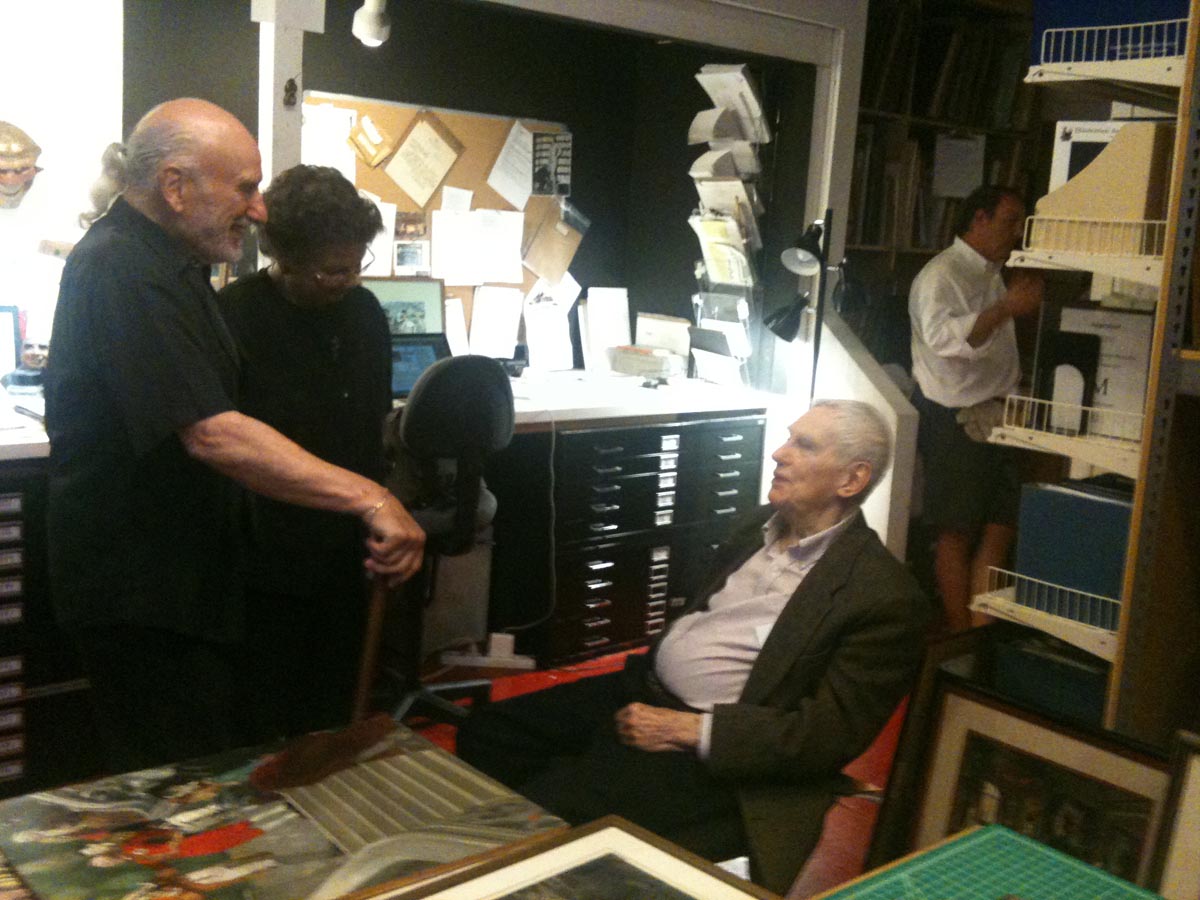

As if a long lunch in this magical place with these wonderful people wasn't enough of a birthday gift, we were joined afterwards by Murray's lovely wife Carol and Eric Fowler, the genial Collections Manager of the Society, who suggested we head upstairs and take a look in "the vault".

Here are Murray and Carol Tinkelman chatting with Bob Levering near Eric's work space in the Collection Room. You can see Eric heading into the deepest, darkest part of the collection in search of some original Robert Fawcetts for us to look at.

Here's Bob Levering, age 91 and one of the sweetest people I've ever met. I had brought along a dozen or so colour print-outs of Bob's illustrations from his Cooper studio days of the '50s for us to discuss, and he was just so pleased to see them. His originals are long gone and I suspect he probably doesn't have any tearsheets anymore... so he was really appreciative to see those 'old friends' again. Propped up behind Bob, a Robert Fawcettoriginal from Collier's magazine, circa 1951.

With Eric's assistance, we soon had an original Charles Dana Gibson and a James Montgomery Flagg to compare. Murray wanted to make a point about why Gibson was such a superior draftsman. I wish I had recorded that conversation, but frankly I was too overwhelmed by being immersed in the whole experience to do much more than snap a few blurry pictures with my phone.

Before we knew it Eric was looking at his watch and saying, "Well folks, I'm afraid I have to close up shop for the day." Suddenly it had become 5:30 -- our little group had just spent the entire afternoon happily chatting away and completely lost track of the time.

Here are Murray and Carol leading the way back down to the main floor. Two in front of Murray hangs an original Mitchell Hooks (in all the excitement I'd forgotten to take a picture of Mitch!) and just beyond it, on the next wall going down the stairs, a typically outstanding space scene by Robert McCall.

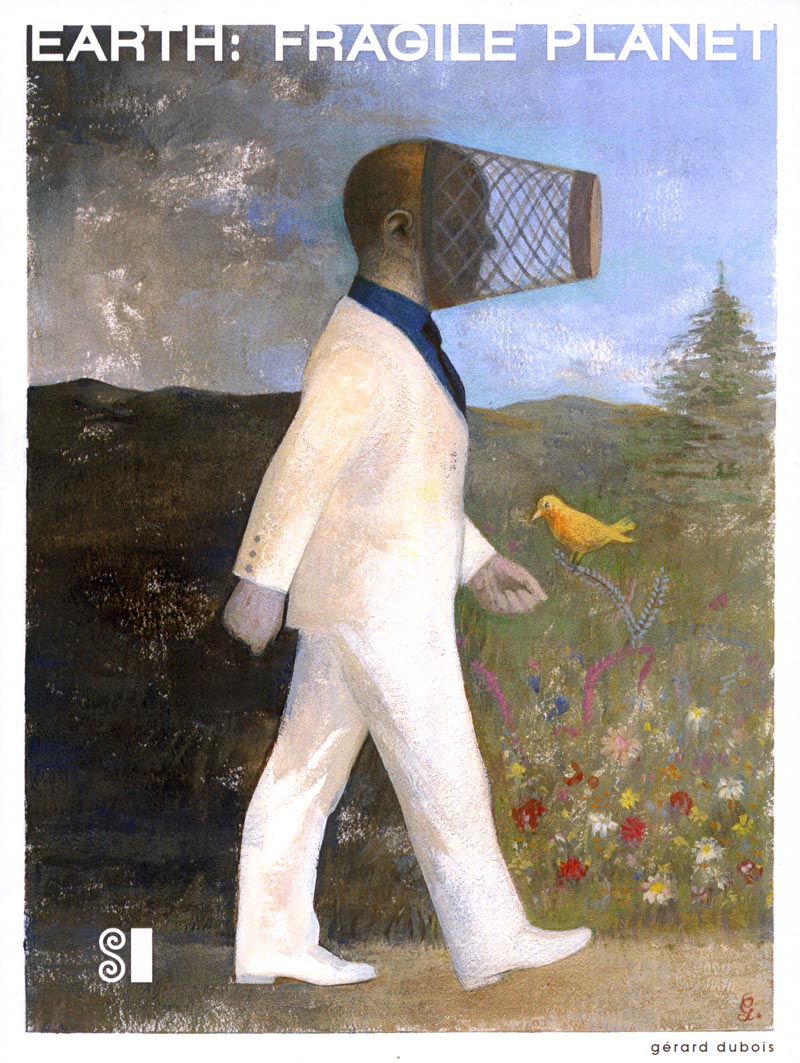

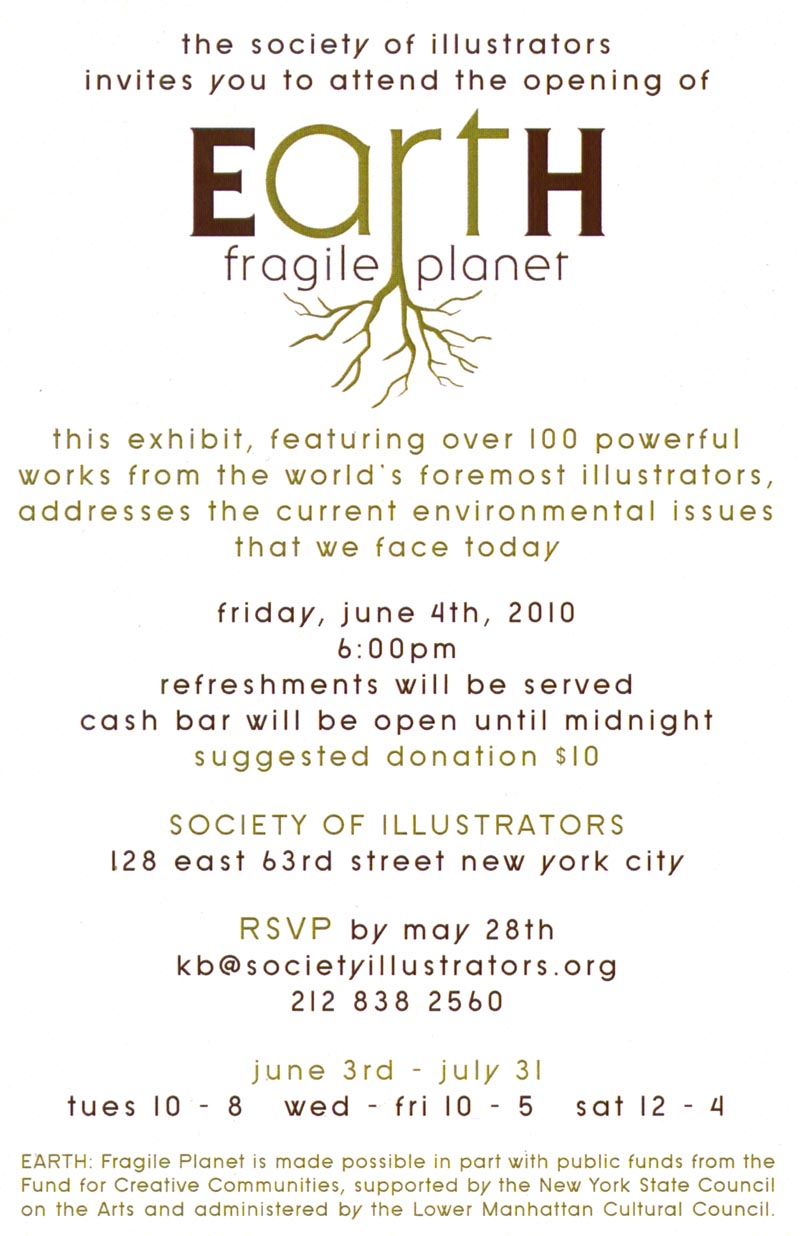

Its entitled "Earth: Fragile Planet" and showcases the work of a wide array of some of the best artists currently working in the business.

Way back at the top of this post I showed a piece Murray did for the New York Times Op-Ed page back in 1972... and here I found the original, hanging just inside the entrance of the gallery at the front of the show. Murray explained that with the current crisis involving BP down in the Gulf Coast, this piece seemed, nearly 40 years later, sadly relevant and appropriate once again.

We took our time wandering around enjoying the tremendous variety of styles and executions in the 120 pieces that comprise the Earth: Fragile Planet show. The intent was to give artists "a forum to set forth their personal views about the state of the world and the environment" and I think it succeeds magnificently.

Here are Murray, Carol, and Eric in the middle distance at left and Bob Levering in the background.

The show opened on Thursday June 3rd and will be in place at the Society of Illustratorsfor 9 weeks. If you are in a position to do so, I encourage you to drop by the Society at 128 E 63rd St. and spend some time taking it in (and if you can, make your way upstairs and see the show in the dining room, too!).

Here are the important details...

And with that, my lunch with Murray Tinkelman came to an end. As we lingered by the front entrance saying our goodbyes, I suddenly felt compelled to embrace this fine fellow. Reaching out for him I said, "C'mere Murray - its my birthday - I gotta get a hug from Murray Tinkelman on my birthday." Murray laughed and, wonderful guy that he is, gave me a great big, genuine, warm hug. I said my final goodbye and wandered away, back toward Central Park. I needed some time to mull over all the details of this remarkable day.

Murray, Carol, Bob and Mitchell... Eric and all the other friendly, interesting people I'd met at the Society, and their kind and cordial treatment of me... all that stunning artwork I'd come in such close contact with... it was all a little overwhelming. It was the best birthday gift I could ever have hoped for!

(Source: murraytinkelman.blogspot.com)

Until later,

Jack

ARTS&FOOD is an online magazine dedicated to providing artists and collectors around the world with highlights of current art exhibitions, and to encourage all readers to invest in and participate in “The Joy of Art” and Culture. All Rights Reserved. All concepts, original art, text & photography, which are not otherwise credited, are copyright 2017 © Jack A. Atkinson, under all international, intellectual property and copyright laws. All gallery events', museum exhibitions', art fairs' or art festivals' photographs were taken with permission or provided by the event or gallery. All physical artworks are the intellectual property of the individual artists and © (copyright) individual artists, fabricators, respective owners or assignees.

Trademark Copyright Notice: ©ARTSnFOOD.blogspot,com

©ARTS&FOOD, ©ARTSnFOOD.com, ©ARTSandFOOD.com, ©ART&FOOD, ©ARTandFOOD.com, ©ARTnFOOD.com)